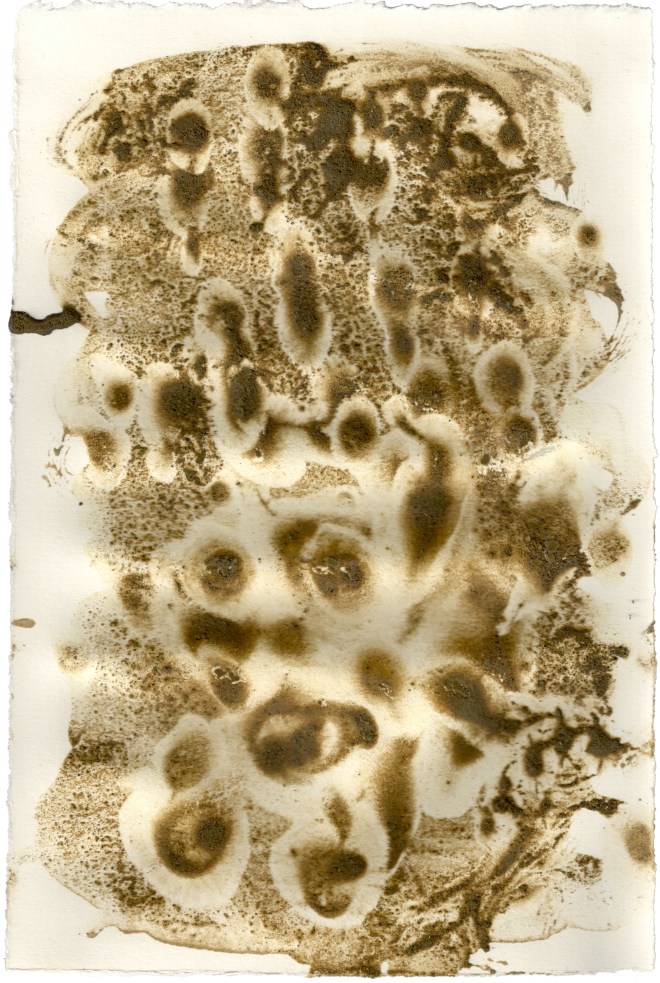

Did this this morning. Sumas Mountain ochre, egg yoke, bacon grease, water.

Author: Christopher Patton

On abandonment

Been my work to report from the inside of what Winnicott calls “unthinkable anxieties” or “primitive agonies.” Others have said “annihilation terror.” The feeling I’m about to be snuffed out, next instant, makes no sense I’m going on being at all. Whole universe withdrawing from me in the mode of female rejection. Times I’ve wanted to help the process along, step in front of a truck. No, not now, not for a long time – I’m okay. This is a field report not a plea.

All the childs feel them. Belongs to being human, animal part stone part star. Most of us probably have echoes in us, form of nightmares, neuroses, phobias, premonitions. And some us saints been left with ’em more wholesale.

A rupture with my lover (screwy and I hope brief) and another with my mother (my choice and I fear for good) have me in a rough pinch right now. Add an intrusive procedure this AM to look at my bladder by the only route on offer – I fucking wept, not with pain, it hurt bad but was the intrusion got my sorrow on – and I really am in a way this evening.

A life’s work, wow, yeah. Tracing and reporting on it. How I hollow out inside. Or how the whole world, every perceptible instant, birdsong say, recedes from me, becomes alien, taunting, hostile.

Those who got stuck at this juncture with me will know it already. Those who made it through may not remember it. The forgetting is salutary, why should I ask you to remember. I have no good answer to that, right now.

But also, points of exit, relief. This terror, when I’m in it, is my ground – I’m looking to speak my ground. But also to find the ground under my ground and to soar from it.

Well. I’m sitting at Menace Brewing, trying to work on my Old English ms, due sooner than I fear I can manage, but this blog post called. I want to write about Winnicott, kindest of the psychoanalysts, but if I start I won’t stop, and I’m away from my books anyway. His interfusions with the buddhadharma are many. I have a feeling he underwrites, already, my Dura Mater.

And sorrows of these women I don’t understand, and have had a hand in, and feel held to account for. Sorry I’m mysterious there. The only life I get to strip mine here is my own.

I’m a man nearing 50 with a squalling inconsolable babe in me.

This grabbed (later) from Maggie Nelson’s Argonauts:

As concepts such as “good enough” mothering suggest, Winnicott is a fairly sanguine soul. But he also takes pains to remind us what a baby will experience should the holding environment not be good enough:

The primitive agonies

Falling for ever

All kinds of disintegration

Things that disunite the psyche and the body

The fruits of privation

going to pieces

falling for ever

dying and dying and dying

losing all vestige of the hope of the renewal of contacts

Mothers they got it tough. I don’t know how any of them do it. And its going wrong, well, Winnicott thought some of the world’s hurt could be explained there.

I say to me, you got to mother yourself, no one else will, you got to father yourself, no one else will. Everything that is here is here with you. What’s the practice of that though.

A lifetime looking, and I’ll be honest, not not finding.

Hard to remember when the fear sweeps through you as nebula.

Dura Mater

Been working on a new project, Dura Mater, tough mother. Membrane enveloping and protecting the brain and spinal cord. First poems to come have been visual. A cruddy ochre salvaged from nearby Sumas Mountain, ground under the tutelage of H. in mortar and pestle, watered and binded with some eggyoke, and smeared on wetted paper by finger and rocked about a bit.

This one wasn’t coming right so I planted my whole palm on it, the way I do sometimes on my mother’s frameless photo on my altar to comfort her, as if by magic I could somehow, and that again – patting, petting – and beings began to come.

Click once for some granularity, again for more. Some text to come.

Click once for some granularity, again for more. Some text to come.

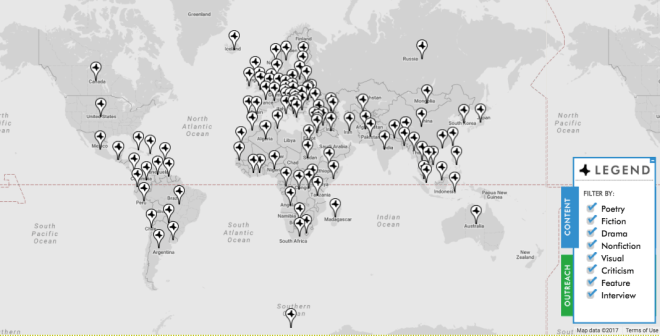

Messages across seas

Delighted to share with you a translation just now out in the journal Asymptote. I love this journal, its global intention attention & compass. Check out this map of their scope & multiplicity.

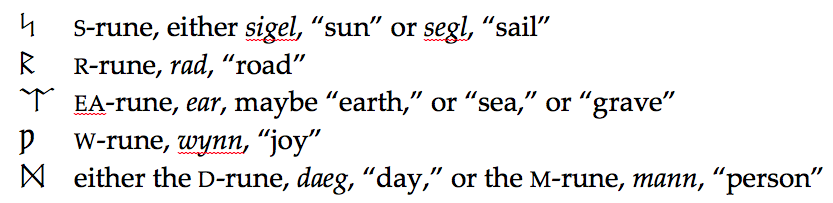

My little poem is a pre-modern throwback in an issue otherwise on translation’s front edge. (Okay, there’s some Tzara, too, but he’s still.) Grateful they thought to find room for it. Thematically it does I guess fit an issue called “People from the In-between.” It’s got people at a loss, unbridgeable textual gaps, & runes – runes how to make meaning from which is all dispute.

Well see what you think it’s here. Poem I’ve called His Message and usually goes by The Husband’s Message. With floating footnotes, & the Old English, & me reading said Old English badly, should you wish to go there.

Whole issue’s rad. Especially worth your time and heart, the special feature on “literature from banned countries,” i.e. those 7 or 6 singled out by the present US administration’s unconscionable incoherent & never mind that they’re unconstitutional travel bans. I’m having trouble finding the section as a cluster, but go to the headline piece, then you can just wander over borders, as surely mostly we should be.

Wander or sojourn or flee as our luck has it. I avoid the word “privilege” as calcified but I am luck-filled. Many on the map above are not. Many pressed against borders are getting fucked by the stick of the world. May you come to places of rest. You should have, & it’s in the UN Declaration of Human Rights, Trumpwad, so you’re a signatory, you should have a place to live that’s safe for you to love & work & love more & live & die meaningful lives and deaths.

Reading this article in The New Yorker has shocked the living shit out of me.

These women girls & men are moving up Africa along the old slave-trading routes. What they endure on the journey & when they arrive, if they do arrive, seems, to this far away safely sheltered reader, no less than what the slaves did in olden days, when they were fuelling the economic growth of the Americas.

More to say here. Such as, bringing it to my nonfiction workshop’s notice, putting it beside Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me, his effort to broaden a indictment of systemic American racism into a critique of global inequality, including climate change. That’s for another post. God & damn it’s all connected. Where to snip the thread? Thank you friend. May I call you friend? If you’ve read this far.

Maggie Nelson, The Argonauts

Can’t tell you how moved I am by this book. Opens my head and heart and spirit and helps me to love the great bawling mess of meat and lust and loss and peace all at once I am. I hope it speaks to my students also. Assigned it because they are, as a body, far more engaged with and alert to questions of gender, identity, fluidity, than I, and I wanted a book that would meet and maybe challenge us all there.

We’ll see how it goes next week. I’m guessing it will. Here are the assignments I put together for my creative nonfiction students this morning.

Journal no. 1

On page 5 Nelson makes the first reference to her book’s title. “Just as the Argo’s parts may be replaced over time but the boat is still called the Argo, whenever the lover utters the phrase ‘I love you,’ its meaning must be renewed by each use.” So we have an image of a voyaging entity that changes in all its parts and yet persists under a single name. And Nelson has named her book, not for the boat, but for those who voyage on it. What is she saying (proposing, hazarding, trying out) about love here? Is the image of the Argo, the Argonaut, applicable to anything else in or about the book?

Journal no. 2

The content of The Argonauts affirms fluidity over binaries and rigid categories – continuities. Gender is fluid. Eros itself is fluid, bonding lover to lover, parent to child, human to animal. Meanwhile the form of the book is full of discontinuities. Every time we move from one collage element to another, we leap across a gap. (Often even within a collage element, there are gaps to be leapt.) What do you make of this difference between the book’s content and its form? How might it serve Nelson’s purposes?

Writing no. 1

Begin a collage essay by writing two discrete (they need not be discreet) collage elements. Each can be about whatever you like, but they should be substantively different from each other, in content, technique, tone, theme, and/or diction. The differences between them should be alive – you, we, should feel a pulse of curiosity or excitement or WTF as we move from the one to the other. If you don’t feel that excitement, start over, because you’re not going to want to keep working with this material. ¶ Other pointers. Remember the distinction between scene and exposition. When you’re doing scene, use your arsenal of fiction-writing techniques; rely on concrete significant details; embody your meanings in acts and events. When you’re doing exposition, avoid banal generalities, make your thinking interesting, fresh, alive, your own. Feel free to tear a page from Nelson and incorporate found materials – Deleuze, Irigaray, Plato, Lady Gaga.

Found poem (w/ rune painting)

A near perfect haiku came from my love by text earlier this eve.

Im making my moms

moms cake for dessert , it

is called “my cake”

I get pissy about 5-7-5 for haiku in English. Wordy. Haiku’s genre for us not form, moment of unanticipated in-seeing. Count your blesses! not your sylls!

Also the search has been on since at least Kerouac for authentic American haiku. Now and then one’s found, and this looks to me like one.

Serendipitous also, her rune tanka, 5-7-5-7-7, pigments made of ochres from the whole planet. No fool I haven’t counted the sylls. It’s a five-realm rainbow.

H. painted it in quick accord with these runes in the OE poem “His Message.” The which no one knows how for sure to read

Have a trans. of it coming out soon in Asymptote, will post a link of it when up.

A first home for SCRO

I’m thrilled to have a bit of SCRO in this upcoming exhibit at the Minnesota Center for Book Arts. Case you’re somewhere round Minneapolis, the deets:

Asemic Writing: Offline & In the Gallery

March 10, 2017 – May 28, 2017

MCBA Main Gallery

Opening reception Friday, March 10; 6-9pm

Asemic writing is a wordless semantic form that often has the appearance of abstract calligraphy. It allows writers to present visual narratives that move beyond language and are open to interpretation, relying on the viewer for context and meaning. Beyond works on paper, asemic writing enjoys a growing presence online and continues to evolve with new performance-based explorations and animated films.

Asemic Writing: Offline & In the Gallery, curated by Michael Jacobson, is the first large-scale exhibition of asemic art in the United States, featuring the work of over 50 international artists who together create an eclectic assemblage of inventing, designing, and dreaming.

Asemic Translations

Saturday, March 25; 7-9pm

Free and open to the public

Join us for a special reading by various asemic artists and scholars, and music by Ghostband. This event is sponsored by Rain Taxi.

A few screen shots from my sequence, SCRO 9am, 10am, 12pm.

Comedy, Tragedy, Romance

A handout for my Shakespeare students, late in the game, after we’ve teased a lot of it out in conversation. Trying to draw it together into a sort of whole, without making our thought boxes too rigid.

I. Comedy

Toward a Theory of Comedy

In our discussions of A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Twelfth Night, we speculated that for something (a line, a conversation, a play as a whole) to be funny, three things need to be true:

- There needs to be incongruity – two meanings of a word that clash (a pun), or two conflicting desires in a character, or a situation in which we know something a character doesn’t (dramatic irony). An incongruity can be as small as a word or as big as the whole play.

- We need to feel that things will turn out okay. We can tell no one is going to die, and no one we like will end up worse than they started. A play can give us this feeling by invoking certain genre conventions of comedy. For instance, presented with lovers thwarted by a controlling father, we know we’re in a plot typical of romantic comedy. And when the lovers marry at the end, ideally as part of a multiple wedding (wild erotic possibilities set loose in the play, some of them quite transgressive, are here put back in their cages, or on their leashes) that plot structure is completed, and the genre confirmed.

- Our sense of fair play needs to be satisfied – characters will get about what they deserve. Again, genre conventions reassure us here, even when things are going badly for the good guys, and well for the bad.

Interestingly, tragedy differs from comedy mostly on the second point. Tragedy is full of incongruities, and the downfall of the tragic hero feels harsh to us, but not unjust (fair play). But we have a sense of large hidden forces arrayed against the hero and driving the action inexorably forward. This won’t end well and we know it from the first line or two. So the incongruities are mostly not funny, and the justness of the hero’s fate prompts sadness and seriousness, not exuberant good cheer.

Genre Conventions of Shakespearean Romantic Comedy

The major conventions of Shakespearean Romantic Comedy (adapted from Debora Schwartz’s page for ENG 339 at California Polytechnic State):

- The main action is about love.

- The would-be lovers must overcome obstacles and misunderstandings before being united in harmonious union. The ending frequently involves a parade of couples to the altar and a festive mood or actual celebration (expressed in dance, song, feast, etc.).

- Often it contains elements of the improbable, the fantastic, the supernatural, or the miraculous, e.g., unbelievable coincidences, improbable scenes of recognition/lack of recognition, willful disregard of the social order (nobles marrying commoners, beggars changed to lords), enchanted or idealized settings, supernatural beings (witches, fairies, gods and goddesses). The happy ending may be brought about through supernatural or divine intervention or may merely involve improbable turns of events.

- There is frequently a philosophical aspect involving weightier issues and themes: personal identity; the importance of love in human existence; the power of language to help or hinder communication; the transforming power of poetry and art; the disjunction between appearance and reality; the power of dreams and illusions.

II. Tragedy

Suspension of Disbelief

Right in front of you, a general named Othello is throttling his wife, Desdemona. Why don’t you call 911? Because you know it’s not real. But if you know it’s not real, why do you feel anything? Check your heart rate, your breathing, your muscle tension – you do feel something.

Drama depends on a suspension of disbelief. We believe and don’t believe that what’s happening is real. We know it’s real and we know it’s not real. We suspend our disbelief but our disbelief is still there. All dramatic forms depend on this paradox to work, but the paradox comes especially clear with tragedy, because the stakes are so high, and because in a theatre, there’s no screen to distance you from the action – only an invisible fourth wall some characters (e.g., Puck, Feste, Hamlet, Iago) may break.

Aristotle on Tragedy

Aristotle asked, why do we like to see things on stage, for instance King Oedipus turned to a beggar with his eyes gouged out, we wouldn’t want to see for real? In his Poetics he suggests two theories –

- Pedagogic. It gives us pleasure to learn, especially when we can learn about misfortune without suffering misfortune. Watching Othello, we can say, “ah, that’s what happens when you give in to jealousy,” or “so, that’s how it goes when you don’t listen to your suspicions about an underling,” or, “okay, that’s what eventually happens to someone from a marginalized group, no matter how well he fulfills the dominant culture’s demands of him.” By this theory, we know more about what it is to be alive, without having had to suffer (much) for the lesson.

- Cathartic. Catharsis means purgation. Tragedy arouses pity and fear in us through the action of the play and then discharges it through the resolution. What we see makes us sadder and wiser, but we also feel a kind of quiet and release. The Greek word katharsis had both a medical sense – purging, i.e., vomiting up something toxic – and a sacral sense, purification, i.e., being cleansed of impurities. Did Aristotle mean we’re purged of pity and fear the way a patient is purged of a poison, or we’re purified of pity and fear the way a religious observant is cleansed of obstructive emotions?

Aristotle said some conditions apply to tragedy, if learning or catharsis is to happen. We’ll leave aside most of them. The two we’ll make use of: the hero of the tragedy needs to be larger than life (“better than ordinary men”) but have a tragic flaw. He needs to be larger than life so we identify with and idealize him. (Catharsis only happens if we see ourselves in him.) He needs to have a tragic flaw so we can feel his downfall is just. (We can only learn from what we see if what we see is rational and understandable.) (It’s always, BTW, for Aristotle, a him, Antigone notwithstanding.)

I’m not saying Othello is an Aristotelian tragedy. I’m asking whether it is one. Is Othello a tragic hero? Is he larger than life? Is he brought down by a tragic flaw? (If you say societal forces outside him – “institutional racism” – are ultimately to blame, then no. If you say that that racism, internalized, is to blame, then – oh, an interesting edge we’re on, there.) Does the play raise pity and fear and then purge them? How are you left feeling at the end of a production of it? Does how you feel depend on the character of the production?

III. Some Notes on Romance

Our final play, The Tempest, is now called a romance, but that term wasn’t in use when the play was written and first performed. It was first published as a comedy. The rest of this section is adapted from Schwartz.

The modern term “romance” refers to a hybrid of comic and tragic elements. Because they combine both tragic and comic elements, John Fletcher called them “tragi-comedies.” According to Fletcher, a tragi-comedy “wants [lacks] deaths, which is enough to make it no tragedy, yet brings some near it [death], which is enough to make it no comedy.” Like comedy, romance includes a love-intrigue and culminates in a happy ending. Like tragedy, romance has a serious plot-line (betrayals, tyrants, usurpers of thrones) and treats serious themes; it is darker in tone (more serious) than comedy. While tragedy emphasizes evil, and comedy minimizes it, romance acknowledges evil – the reality of human suffering.

Romance and Tragedy

Tragedy involves irreversible choices made in a world where time leads inexorably to the tragic conclusion. In romance, time seems to be “reversible”; there are second chances and fresh starts. As a result, categories such as cause and effect, beginning and end, are displaced by a sense of simultaneity and harmony.

Tragedy is governed by a sense of fate (Macbeth, Hamlet) or fortune (King Lear). In romance, the sense of destiny comes instead from Divine Providence. Tragedy depicts alienation and destruction, romance, reconciliation and restoration. In tragedy, characters are destroyed as a result of their own actions and choices; in romance, characters respond to situations and events rather than provoking them. Tragedy tends to be concerned with revenge, romance with forgiveness. Plot structure in romance moves beyond that of tragedy: an event with tragic potential leads not to tragedy but to a providential experience.

While tragedy deals with events leading up to individual deaths, romance emphasizes the cycle of life and death. While tragedy explores characters in depth (emphasis on individual psychology), romance focuses on archetypes, the collective and symbolic patterns of human experience.

Romance and Comedy

The “happy ending” of a romance bears a superficial resemblance to that of a comedy. But while the tone of comedy is genial and exuberant, romance has a muted tone of happiness – joy mixed with sorrow. Like comedies, romances tend to end with weddings, but the focus is less on the personal happiness of bride and groom (the culmination of an individual passion) than on healing rifts within the larger human community. Thus, whereas comedy focuses on youth, romance often has middle-aged and older protagonists in pivotal roles.

Compared to characters in a Shakespearean comedy (or tragedy), romance characters may seem shallow or one-dimensional. But they are not meant to be psychologically credible; their experiences have symbolic significance extending beyond the limits of their own lives and beyond rational comprehension. In romance, the emphasis shifts from individual human nature to Nature.

Other Features of Romance

Romance is unrealistic. Supernatural elements abound, and characters often seem “larger than life” (e.g., Prospero) or one-dimensional (e.g., Miranda and Ferdinand). Plots are not particularly logical. The action, serious in theme, subject matter and tone, seems to be leading to a tragic catastrophe until an unexpected trick brings the conflict to harmonious resolution. The “happy ending” may seem unmotivated or contrived. Realism is not the point. Romance requires us to suspend disbelief in the “unrealistic” nature of the plot and experience it on its own terms.

On listening to another, oneself

Zoketsu Norman Fischer on listening:

- Listen with as few preconceptions or desires as possible.

- Listening takes radical openness to another and radical openness requires surrender.

- Listening turns a person from an object outside, opaque or dimly threatening, into an intimate experience, and therefore into a friend. In this way, listening softens and transforms the listener.

- Listening requires fearless self confidence that is not egotism. It is faith in yourself to learn something completely new.

- To listen is to shed, as much as possible, all of our protective mechanisms.

- Simply be present with what you hear without trying to figure it out or control it.

- To listen is to be radically receptive to others.

- You are aware of all your preconceptions, desires, and delusions, all that prevent you from listening.

- Listening is dangerous. It might cause you to hear something you don’t like, to consider its validity, and therefore to think something you never thought before, or to feel something you never felt before, and perhaps never wanted to feel. Such change in ourselves is the risk of listening, and this is why it is automatic for us not to want to listen.

- To really listen is to accord respect. Without respect no human relationships can function normally.

- So much of what we actually feel and think is unacceptable to us. We have been conditioned over a lifetime to simply not hear all of our own self-pity, anger, desire, jealousy. Our “adult response” is no more than our unconscious decision not to listen to what goes on inside us.

From Taking our Places: The Buddhist Path to Truly Growing Up

So much of being grown up, yeah, is an unconscious choice not to listen to most of what goes on inside.

How to listen and let it, another, oneself, in. Not give it sway but look after it.

Asked before what just sitting following the breath could possibly offer as a response to Trump and what’s happening.

This thought, just now. Trump’s first failure is a failure of inner listening.

I know that sounds 180 degrees wrong. But I mean Norman’s sort of listening – the friendship given another, given to oneself. Trump has no such friend.

The image atop: three Daruma dolls. I saw one last summer in a store window in Toronto and wished for it and … oh, it’s a long story, but my dear friend Barb went to great lengths, and then some more. And over pancake breakfast at the Old Town Cafe a few days ago passed it across the table to me. Daruma = Bodhidharma, Zen founder, spent nine years in a cave listening.

With thanks to Nomon Tim Burnett for passing the text on.

Everything you wanted to know about meter in Shakespeare but were afeard to ask

Given to my Intro to Shakespeare students and now y’all. (Sorry, leaving out the bit where I show how to listen for stresses, and mark them, or show them rather they already know how to listen for stresses, just don’t know they do.)

And here we go. The baseline foot of iambic meter is the iamb: x /

(marking unaccented syllables x, accented syllables / )

The most common variation in an iambic meter is the trochee: / x

Other common substitutions in an iambic meter are

the anapest x x /

the spondee / /

Occasionally you’ll see the pyrrhic x x and it’s usually paired with the spondee like so x x / / and that’s sometimes also called a double iamb.

Only other foot possible, in English, is the dactyl / x x and you won’t see it in an iambic line. If you do you’ve grouped the stresses wrong. Erase your foot divisions and start over, remembering to maximize the number of iambs.

Similarly, if you come up with this x / x or this / x / as a foot, you’ve gone astray somewhere, unless you’re scanning Greek or Latin verse for quantity, which you ain’t. Back up and start over.

Sometimes at the end of a line you’ll have an extra unstressed syllable, and want to join it to the final iamb to make a foot like this x / x don’t. Leave it there. It’s not lonely, it’s a syllable, not a kitten. If you see a kitten, rescue it.

Moves to watch for, and effects they’re thought to have. An initial trochee

/ x

Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer

creates emphasis by leaning into the words to come. A mid- or end-line anapest can lend speed, momentum, naturalness –

x x /

The heart-ache and the thousand natural shocks

A spondee creates emphasis a bit differently than the trochee,

/ /

No more – and by a sleep to say we end

pounding its fist on the words right at hand. The pyrrhic-spondee pairing (double iamb)

x x / /

with a bare bodkin? who would fardels bare?

is an interesting move, softening, yielding, then hitting hard. Take a look at this moment in Hamlet’s monologue; can you discern what the variation does, here? How would you perform it?

Last thing, we sometimes see trochaic meters in these plays – songs and spells, mostly. Trochee world is Bizarro world – English is biased to the iambic, so when you go trochaic, you go to the strange. In a trochaic meter, iambs are the most common substitution, and feel like an unexpected or unaccustomed softening. No anapests here but dactyls have become possible. Spondees and pyrrhics rock on, as before.

To review (and add a little). Feet that make the basis for meters in the plays:

iamb x /

trochee / x

Feet that can be variations in those meters:

anapest x x /

dactyl / x x

spondee / /

pyrrhic x x

How to describe the length of a line

one foot monometer four feet tetrameter

two feet dimeter five feet pentameter

three feet trimeter six feet hexameter

To give a full description of the meter of a line, identify the baseline meter (dominant foot and number of feet) and any substitutions. E.g., “iambic pentameter with a spondee in the fourth foot” or “trochaic tetrameter with a dactyl in the third foot.”

The marks, the terms, are a pain, I know, but they’re a means to an end. A violinist doesn’t learn to read sheet music so she can read sheet music. She learns it so she can play a Bach concerto.

Lastly, note we’re marking meter here, not rhythm, which is a subtler business altogether. There’s a way to mark it but we’re not going there. Fortunately, as speakers of English, you live in its rhythms as fishes in water, so just trust your sense of the character as a living human being, speaking to others the same. The meter is in there, lending order quietly, almost invisibly. When reading these lines, don’t be a robot, be a person.