I thought I would post here, with her husband Steve’s most kind permission, the remarks I made at the memorial this weekend for Elise Partridge. It was a beautiful occasion, the afternoon. Our seats arranged such that our seeing went out the frames of the windows and frames of wood and frames of stone and frames of shore pine and out over ocean into the frameless mountains. (I have it in mind because two days later Stephen Burt spoke in that same space, differently em-placed, on the poetry and poetics of place.) One might almost feel one was a spirit passing through bodily frames, one, another. The words I said were about these.

In the weeks around Elise’s death I’ve been talking with some of my students about animism. The thought — to be a bit simple about it — that the world is alive. Every part of it and the whole of it. Which I think might mean, if it’s true, that when you go, you’re not really gone, you’re just differently here.

I start with that because I haven’t been able to get my head around it very well. Elise — here. Elise — gone. It’s the most elemental thing. We get to live so we’ve got to die. And, as Elise leaves the tangible world, I am finding it makes almost no sense to me at all. I keep looking for ways to find her not gone but instead differently here. And so maybe all I’ve got for you is four and a half more minutes of magical thinking.

It’s a sort of thinking Whitman was fond of. And Steve’s asked me to read a late poem of his. And so I guess through him Elise is asking me to read a late poem of his. It’s called “The Last Invocation” and it goes like this.

1.

At the last, tenderly,

From the walls of the powerful, fortress’d house,

From the clasp of the knitted locks — from the keep of the well-closed doors,

Let me be wafted.

2.

Let me glide noiselessly forth;

With the key of softness unlock the locks — with a whisper,

Set ope the doors, O Soul!

3.

Tenderly! be not impatient!

(Strong is your hold, O mortal flesh!

Strong is your hold, O love.)

Whitman, who said we could find him underfoot. I don’t think of Elise as under our boot soles — I think she’d find the notion undignified — so much as behind our eyes. Entering our vision to sharpen it with us. Forgive me for going back to my class but they’re on my mind because they had to bear with a teacher thrown off his game for a while by grief. I might put it to my class this way. If the proposition of animism is, oh, when you go, you’re not really gone, the problem for us moderns is, yeah, we’re here, but we’re not really here.

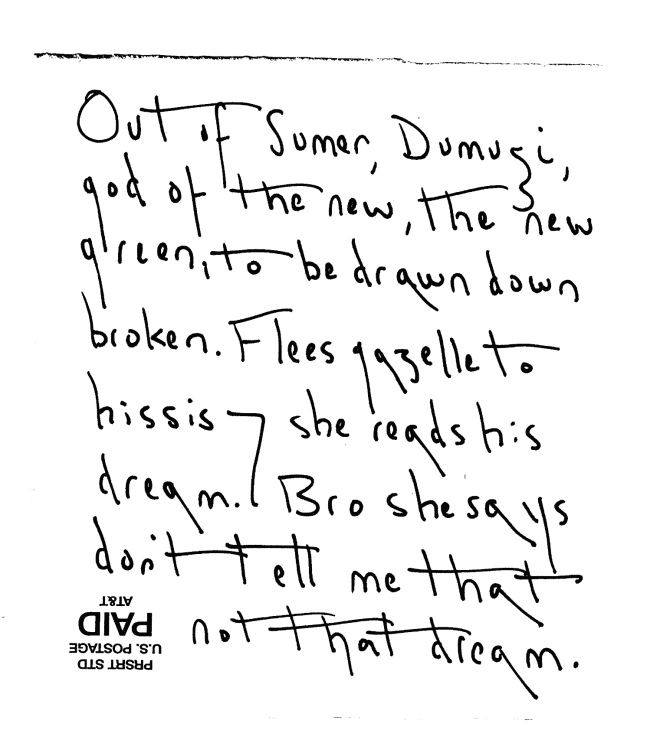

That’s a problem Elise concerned herself with. In her work, in her life. Maybe the problem though I don’t want to presume. What, every one of her poems asks, stands in the way of seeing more clearly, hearing more kindly, touching more tenderly, feeling more feelingly. And go — the poems say, to whatever that what is — go stand somewhere else, there’s a life to be lived, fully, lived well, lived lovingly. The first lines of the first poem of her first book —

Nothing fled when we walked up to it,

nor did we flinch.

What a note to start a life in poetry on. “Everglades” is the poem. It has a vision of that swamp as a wild and wildering democracy —

Tropical, temperate, each constituency spoke —

the sunburned-looking gumbo-limbo trees

nodded side by side with sedate, northern pines.

“Gumbo-limbo trees”! What better evidence of a life well lived? (The phrase, I mean.) The line following —

Even the darkness gave its blessing

A darkness from which I’d like to think Elise blesses or raises an eyebrow at us.

I wanted to touch on her e-mails, how they quivered with joy on one’s behalf, and with outrage at banality, idiocy, herd mind, also how they made the exclamation point safe for human perception again — there may have been seventeen of them but you knew each was uniquely meant — but I’m about out of time.

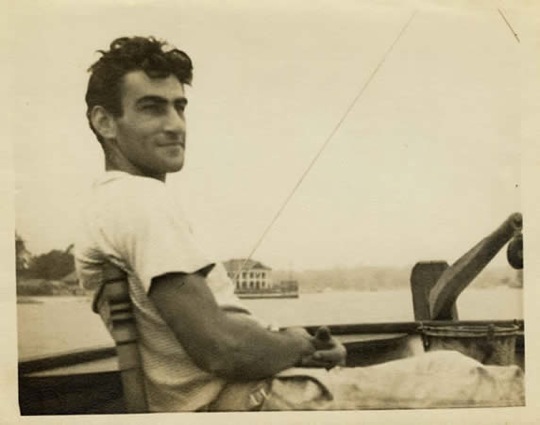

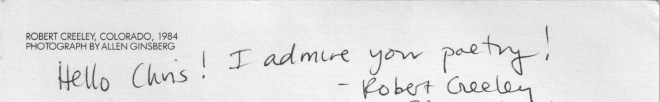

Just this — a postcard from years back, after Steve and Elise had looked after my house and cat on Salt Spring, one of many times. I still have it on my fridge. It’s a photograph of Robert Creeley taken by Allen Ginsberg at a diner in Boulder, CO.

Ginsberg’s inscription: “I wanted to focus on a sharp clear eye — Robert Creeley’s friendship.” Elise’s inscription on the back begins: “Hello Chris! I admire your poetry! —Robert Creeley.”

Elise and I had gone down different paths aesthetically, and at this point in our friendship, she was feeling really kind of pretty unsure what the hell I was up to. And yet she found a way to express, with grace and class and decency, and without dishonouring her own instincts, encouragement and faith in me.

That’s love. That’s the love of a friend for another. It’s a rare thing and it doesn’t die. I don’t think it does, I really don’t.