Another from Horsetail Rhizome. I wrote it about Dumuzi, my 2020 book of poems, for a reader Gaspereau Press made in lieu of the in-person promotions – launches & tours & the like – that had (because pandemic) migrated online or just gone. The questions are Andrew Steeves & the answers me. ¶ Find the whole reader here.

What interests you about these figures from Sumerian mythology, Dumuzi & Inanna? Is there something about their story that is particularly relevant to the present day reader?

They seem a long way away, right? What’s that ancient couple got to do with us? Their stories live on in museums, on musty tablets & cylinder seals. I suggested to a class recently, it’s other people’s beliefs that look like myths – your own look to you like axioms. Space & time aren’t myths, right? They’re facts, verified by science. But if Benjamin Whorf got Hopi verb tenses even roughly right, not every culture sees the future as an expanse spreading out from the present wholly apart from mental action. Space time & causality are myth for us: they arrange a world. A myth is a form of mind, often a story form, that has worked for some group of persons to make, on earth, of earth, a world. Myth is psychic terraforming. ¶ I’m writing with my voice, and it’s funny how Apple’s dictation software turns “myth” to math, mess, Matt, met, Ms. As if Apple wanted to get free of myth, and trying to, made materials for a new myth. ¶ I wanted in Dumuzi, which Apple calls And Get Amusing, to touch on the currency of myth. Dumuzi, wistful, curious, inept, persistent, horny, beaten down by his demons & not down for good, is just me. Inanna, his lover, sending him to hell, mourning him, in some versions rescuing him, is me too. A myth is a story you find more of yourself than you knew of in. ¶ And of the world. By currency I also mean money. Dumuzi & Inanna begin in suchness. (Apple: Do news he Andy Nonna begin in suction us.) They are to each other meanings that can’t be sold off. And the story of their going, one then the other, to Hell, is the story of their fall into commodity. Wild grasses become fields of cultivated grain. The grain is cut down & goes to market. Eating the bread, you eat a god. In time grain becomes a unit of measure: in England 7,000 of them made a pound. And no one needs me to say how Inanna’s daughters have been made commodities by a look. ¶ Dumuzi & Inanna fall into the exchange whose present end is capitalism. (Those who describe the benevolence of capital in circulation are recounting a myth.) The insight myth, language & money share is that everything is interchangeable. For a god, that’s the notion that anything can be anything else. For a salesman, it’s how anything can be had for something else. The capitalist gesture, in whose shadow Dumuzi cannot not be read, is a faltering reach for a spiritual fact. The book is, too.

Can you talk a bit about the book’s form, such as the use of word grids & the use of illustrations built up from a single scrap of an envelope?

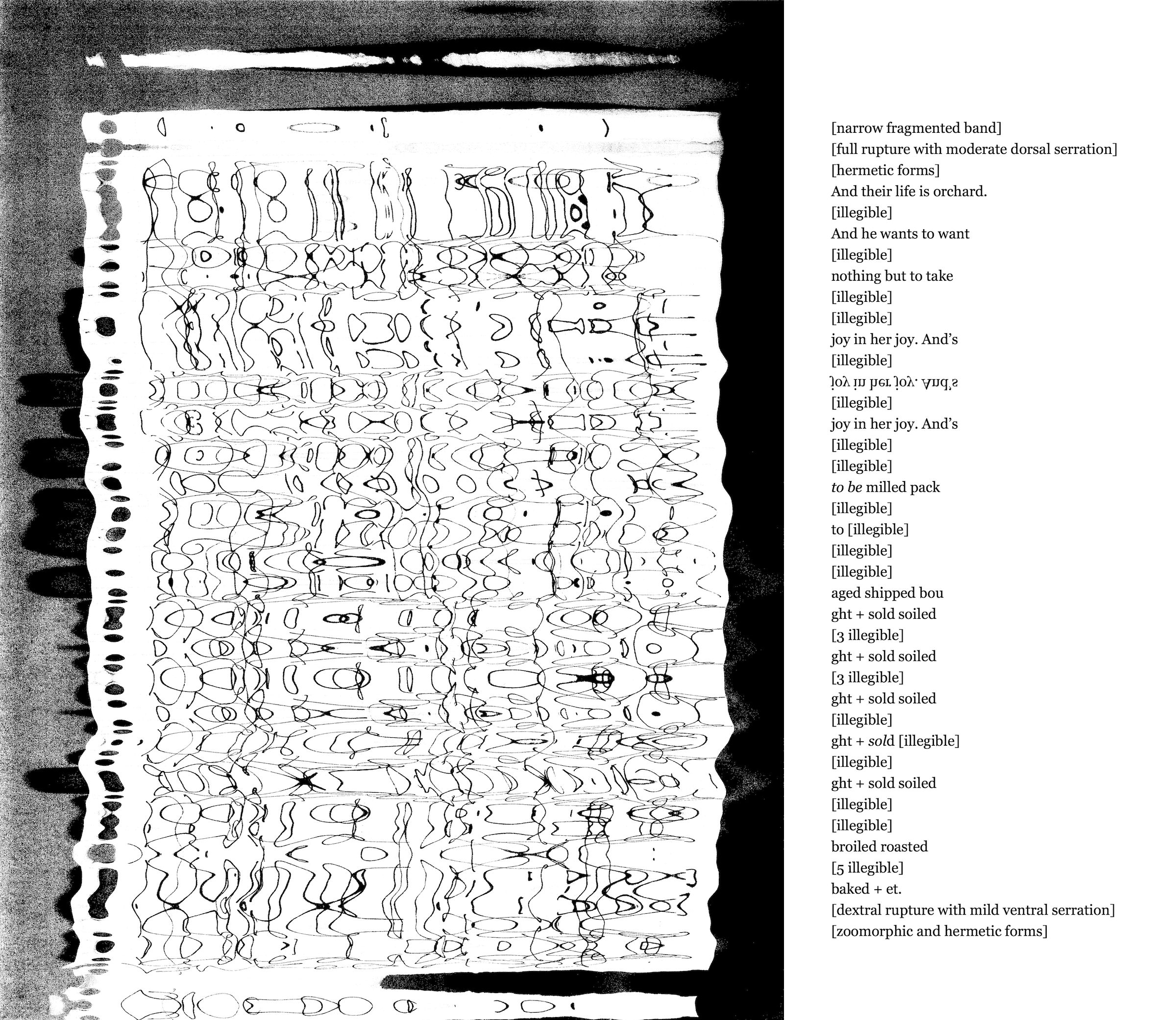

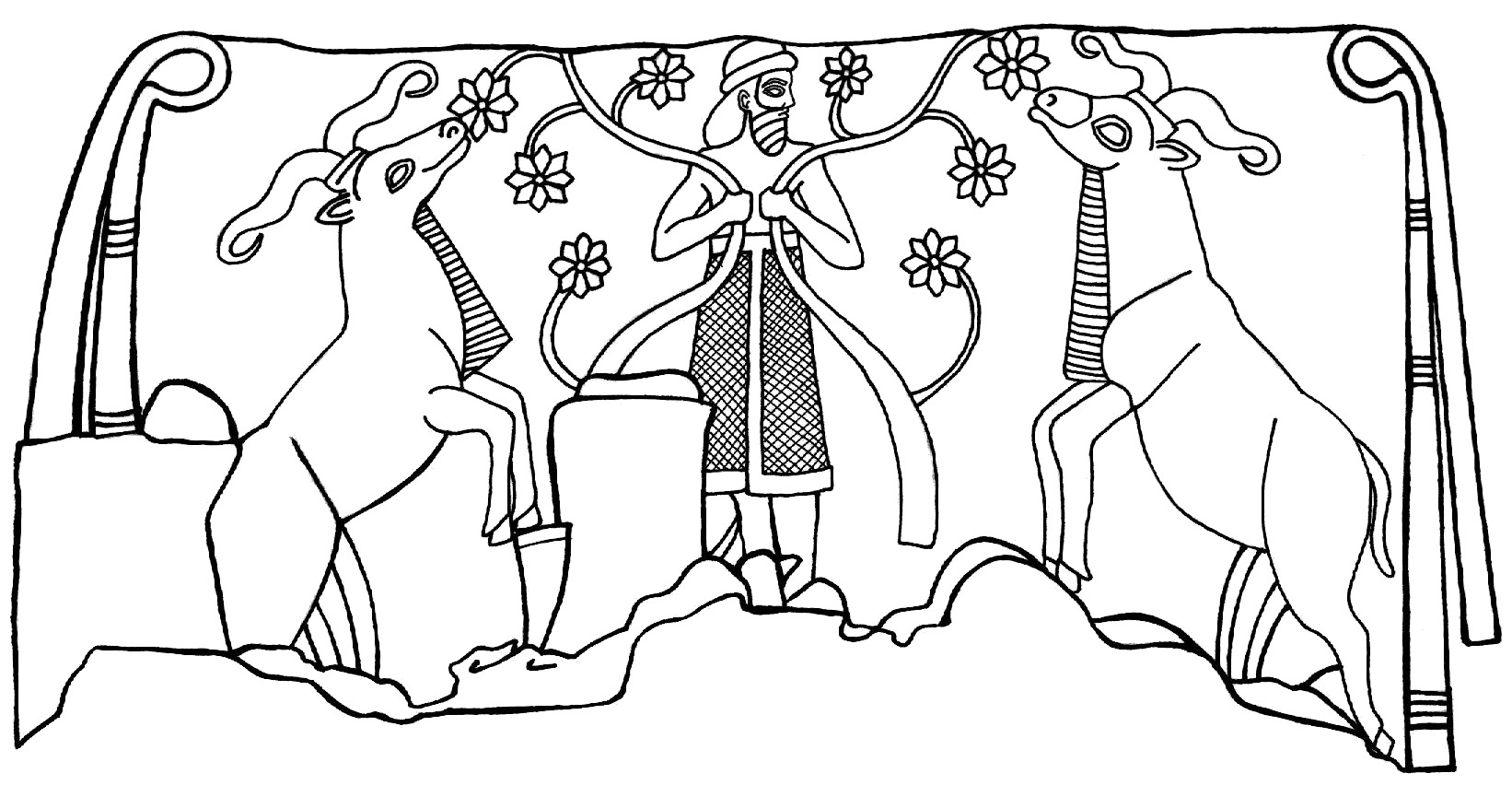

There’s a note in my journal, 20 years or so old, about the structure I wanted for Dumuzi (Apple: Dumb Uzi): “mixed as a weed plot & shapely as a symphony.” Later I read Williams’s Paterson and thought I’d found, in its heterogeneity & dispersed point of view, my exemplar. In the end, Spring and All, where he refracts his language through Cubist compositional techniques, was a better model. ¶ The word grids or “colour fields” are my effort to do something sort-of-Rothko in words. Each of the fields alludes to a place: an orchard, an altar, a gravesite, a marketplace. As important, though, is the place the words are, on the page. The words don’t really do syntax, and the grid invites your eye to move in more than one direction. So the meaning you get depends on choices you’ve made. Similarly, you can start the book at any spot & read from there in more than one order. ¶ The images were the last part of the book to come. I’d been working with security envelope linings for another project, & one started to yield representational figures, a fly, a woman fleeing, a man in meditation. It felt like discovering beings hidden behind the surface of the page. Bringing them out was rescuing someone – myself? a stranger? – from hiddenness. They remind me a bit of the stylized figures incised on old cylinder seals. Those are rescues too, of a form of the mind from forgetting.

held by the Staatliche Museen, Berlin.

The image atop is a detail from a version an illustration in Dumuzi, reworked for Dark Mountain 22 “Ark.” The full massy beast below.