This one came in three parts — a reading assignment, a journal assignment, a writing assignment. The first two meant as robust prep for the third. And I was right they would find it a hard exercise! Maybe the hardest of the quarter. It did ask them to set aside things they’d spent years learning to do well, e.g., staying on topic, making proper sentences.

The exercise (with some of their work to follow) —

1. Reading

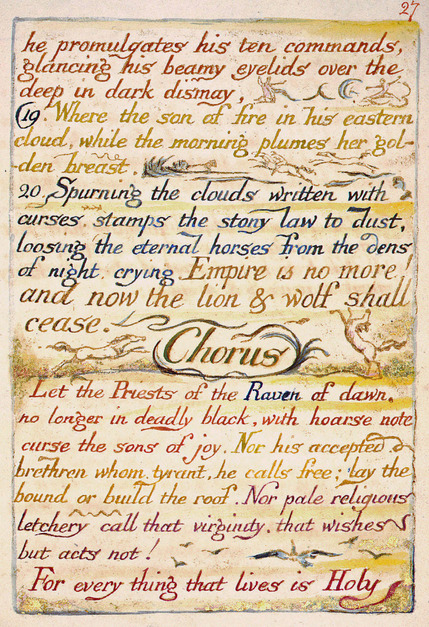

A few pages from Louis Zukofsky’s late word-flower sequence 80 Flowers. Like that one and this one:

STARGLOW

Starglow dwarf china rose shrubthorn

lantern fashion-fare airing car-tire crushed

young’s churning old rambler’s flown

to sky can cut back

a crown transplanted patient of

drought sun’s gold firerimmed branched

greeting thyme’s autumn sprig head

happier winter sculpt white rose

MOUNTAIN LAUREL

Known color grown mountain laurel

broadleaf of acid earth margin

entire green winter years hoarfrost

mooned pod honesty open unvoiced

May-grown acute 5-petal calicoflower cluster

10-slender rods spring seed sway

trefoil birds throat Not thyme’s

spur-flower calico clusters laurelled well

2. Journal exercise

Metonymy is calling one thing to mind by naming another that’s habitually associated with it. For instance, the phrase “red wheel barrow” calls to mind a barnyard, and perhaps a pile of dirt, or hay bales. Pick two individual words in 80 Flowers and describe the metonymic resonance of each — the things it calls to mind by habitual association. NOTE: Some metonymic associations are personal and idiosyncratic — associating a red wheelbarrow with Indians, say, because there’s a mural with the poem on Indian Street. Try to steer away from those associations, and towards associations you can trust would be shared by a typical reader.

(In a class soon after we looked at how context, a word’s neighbour words, draw some metonymic associations into the foreground, and let others recede into the background.)

3. Writing exercise

Each of Zukofsky’s poems consists of eight five-word lines. Instead of coming together into sentences, the words make a sort of kaleidoscopic image of the flower — fragmentary, unparaphraseable. In fact, you might say that the relationship between any two adjacent words is not syntactic but metonymic, interested not in making a statement, but in drawing out habitual associations. Write a poem that uses the same form: eight five-word lines, compound words as you please, words next to each other not to make sentence sense, but to make richly textured juxtapositions.