And, one more of an evening, this excellent essay by Forrest Gander on George Oppen, whose “World, World—” gave me the title to one below.

Category: reading

On erasure practice (II)

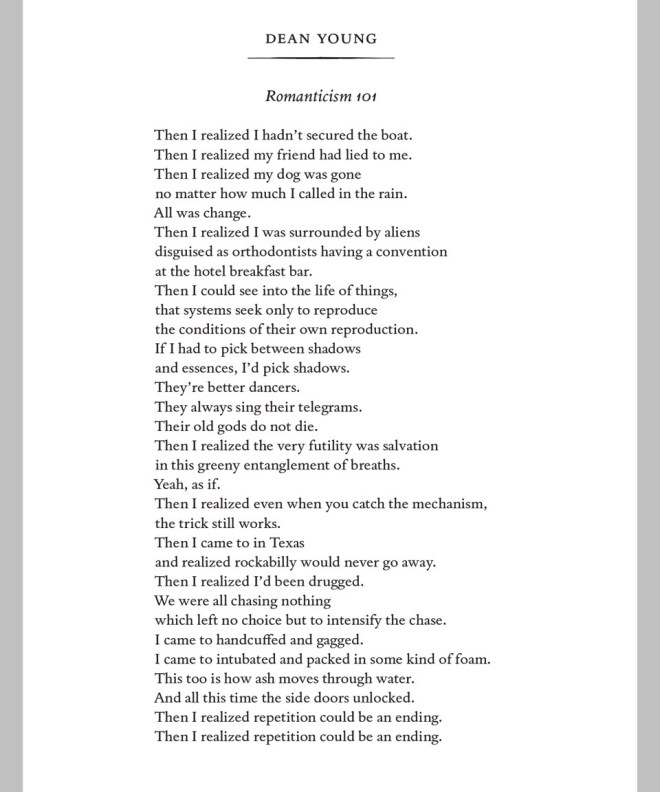

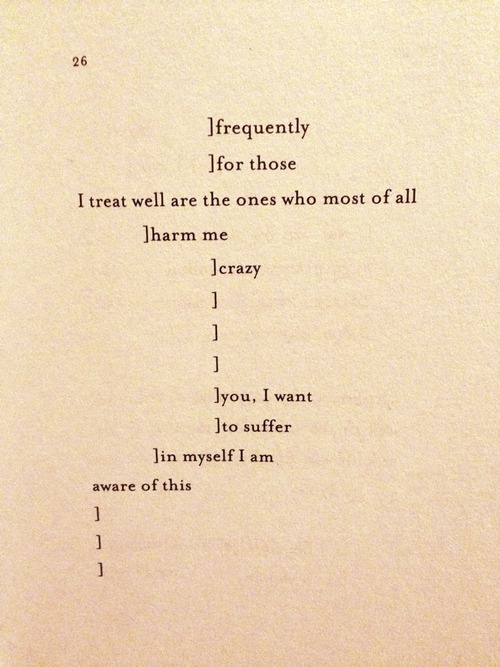

Yestereven, erasure marked typographically, as with Carson and Schwerner, giving a feel of fidelity, though that’s often mock. Also, erasure as palimpsest, as in Bervin’s Nets, the source poem receding into the page but not altogether invisible.

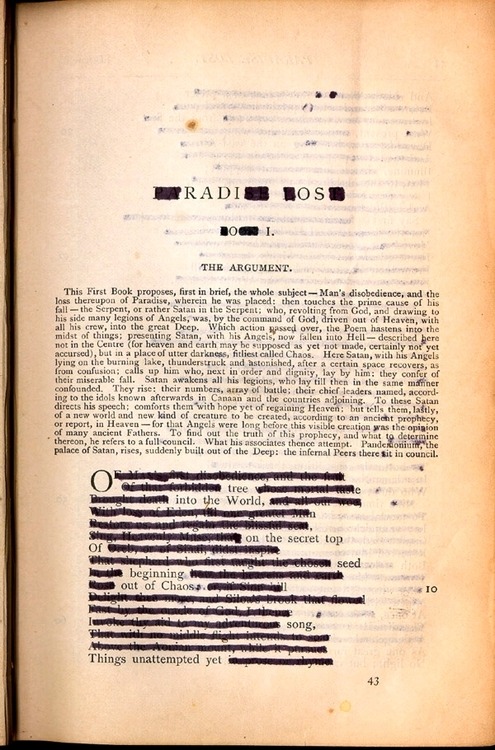

The maybe most austere mode is just to leave the page untouched in its white or creamy presentness. That’s Ronald Johnson’s approach in Radi Os, his seminal erasure of Milton’s Paradise Lost —

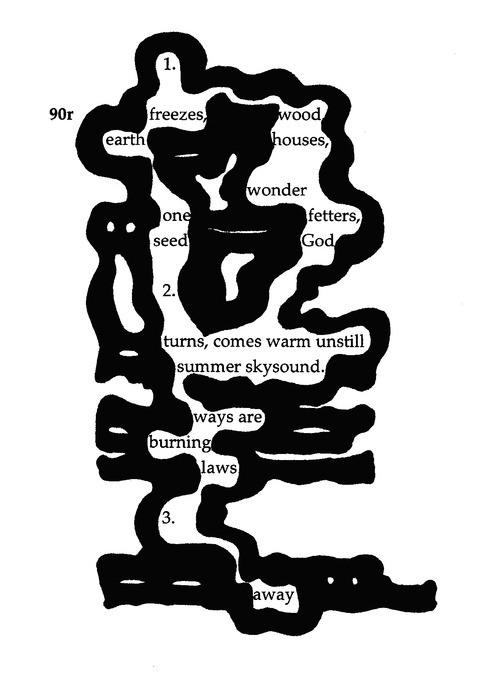

If austere is one end of a spectrum, and illuminative the other, somewhere in the middle’s any practice that retains the erasure marks, making what art of them they propose. Can find a precursor to that in this page from Johnson’s draft copy of Paradise Lost —

It’s a question I’ve messed with some in Overject, erasures I’ve tried out of a minor Anglo-Saxon poem sequence variously called “Maxims” or “Gnomic Verses” or (by me) “Proverbs.” Here I work up the redaction marks to make some funny (and some not-so-funny) faces.

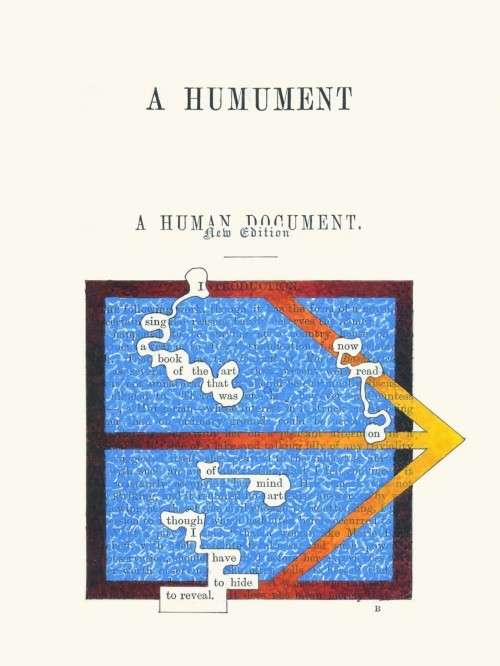

At the illuminative end of the spectrum (both ends and all middles presided over majestically by Wm. Blake) must for sure be Tom Phillips’s A Humument.

Fun fact. My college roommate, Johnny Carrera, my first year at Oberlin, recently had a show with Phillips at MassMOCA. And that’s all for tonight, mes amis, dormez bien.

On erasure practice (I)

Gonna hit erasure practice hard next week with my class. So thought here to summate. So much, to lift a word or three from a forebear to this sprawly lineage, depends on how you mark the missingness of what’s missing.

There’s a typography angel (sic) taken by Anne Carson in her Sappho —

Okay wow so the first clump suddenly recalls me to the borderline people in my life. And the second clump to how I’ve answered them. Well anyway I do love the aberrant slant in the image. Too, Armand Schwerner in his Tablets —

Brackets, ellipses, squares, circles, squared circles, enlisted to mark the polyambience of what’s missing, or imagined to be. Though nothing is really missing, is the message, as I take it, of erasure practice. The blank page a perfect poem no one has ever managed to write.

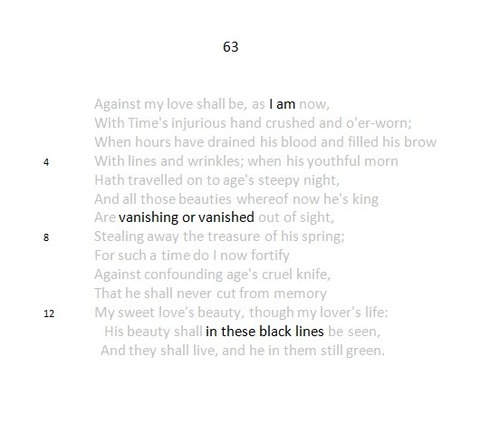

Then there’s the palimpsest, where the new poem greys out, but doesn’t quite white out, the old. Jen Bervin’s erasures of Shakespeare’s sonnets in Nets work here, both stilly

and movingly, as here, where the palimpsest of it flickers in and out. That’s it for tonight, happy sultry (for here) weather all, more tomorrow.

and movingly, as here, where the palimpsest of it flickers in and out. That’s it for tonight, happy sultry (for here) weather all, more tomorrow.

Exercise: Chasing your tail in the word hoard

Write the editors of Imagining Language, from which the passage [they’ve just read] from Joyce’s Finnegans Wake is taken:

At the center of the episode is a hen scratching open a letter in a compost heap…. Any proto-narrative aspect of the Wake is subordinated to its manifestly epic ambition, which is the production of a polyglot interlingua, a massive reservoir from which all languages derive and into which they ultimately return.

In other words, well, in other words. Language itself as the mother of all compost heaps. As in all compost heaps, there are lines of affiliation, lines of ascent and descent. This exercise gets you working with that. It’s some hard work first, and then some free play.

1. Research

First you create a research document. Start by going to the Online Etymology Dictionary at www.etymonline.com. Type in the search window a word you like. I’ll use “compost” (what else). I get several entries, but the one with the most interesting material is

compost (n.) late 14c., compote, from Old French composte “mixture of leaves, manure, etc., for fertilizing land” (13c.), also “condiment,” from Vulgar Latin *composita, noun use of fem. of Latin compositus, past participle of componere “to put together” (see composite). The fertilizer sense is attested in English from 1580s, and the French word in this sense is a 19th century borrowing from English.

I boil this down to the material I think I can use—

Compost. From OF composte, “mix of leaves and manure for fertilizing land.” Also “condiment,” from VL componere, “to put together” (see composite).

That goes in my research document. You do likewise. And do the same with five more words, choosing each new word from the entry you just made. For instance, from my entry on “compost,” I might choose “condiment,” for which etymonline.com gives me this:

condiment (n.) early 15c., from Old French condiment (13c.), from Latin condimentum “spice, seasoning, sauce,” from condire “to preserve, pickle, season,” variant of condere “to put away, store,” from com- “together” (see com-) + -dere comb. form meaning “to put, place,” from dare “to give” (see date (n.1)).

Boiled down, that becomes

Condiment. From L, “spice, seasoning, sauce,” from “to preserve, pickle, season,” variant of “to put away, store,” from com– “together” + dare “to give” (see date).

I move from “condiment” to “season,” from “season” to “timber,” from “timber” to “domestic,” and from “domestic” to “despot.” Boiled down I have:

Season (v.). “Improve the flavor of by adding spices,” from OF assaisoner, “to ripen, season,” “on the notion of fruit becoming more palatable as it ripens.” Applied to timber by 1540s. In 16c., also meant “to copulate with.”

Timber. From OE timber “building, structure,” later “building material, trees suitable for building,” and “trees or woods in general.” From PIE *deme- “to build,” possibly from root *dem- “house, household” (source of Greek domos, Latin domus; see domestic (adj.)).

Domestic (adj.) From MF and L “belonging to the household,” from domus “house,” from PIE *dom-o- “house,” from root *dem- “house, household.” Cognates include Sanskrit “house”; Greek domos “house,” despotes “master, lord”; Latin dominus ”master of a household”; Lithuanian dimstis “enclosed court, property.”

Despot. From OF despot, from ML, from Greek “master of a household, lord, absolute ruler,” from PIE *dems-pota, “house-master,” pota cognate with L for “potent.” “Faintly pejorative in Greek, progressively more so as used in various languages for Roman emperors, Christian rulers of Ottoman provinces, and Louis XVI during the French Revolution.”

2. Mess around

Do whatever pleases you with this research base. Take the most surprising synonym (e.g., that “to season” once meant “to copulate with”) and write a paragraph in which you use the one to mean the other. Write a poem that gets you from the first word in your research document to the last word (how to get from “compost” to “despot”? is there something despotic about compost? something composty about a despot?). Make a paragraph out of nonsense sentences generated by homophonic translation (e.g., for “domestic,” “Be long in thee, how sold, from dumb us, house, from pie …”). Or make a 5×5 panel of words gleaned from your entries, such as

court timber pickle season manure

potent emperor …

Or turn your research into a family tree in which words are arranged as parents and children and cousins and stray animals. Or write a couple of sentences in imitation of Joyce — wringing every possible pun out of every syllable. Or something not thought of here or ever before.

Guest post

Ezra Pound eats worms

This from poetsorg:

Jack Spicer‘s postcard, mid-1950s, announcing a reading of 5 Boston poets: Jack Spicer, Stephen Jonas, John Wieners, Joe Dunn and Robin Blaser

O’Hara’s Lunch Poems

This from citylightsbooks:

On the City Lights Blog: 3 poems from O’Hara’s Lunch Poems as we continue to celebrate the new 50th Anniversary Edition of the book.

The eros aspect

What’s not been touched on yet — the eros of the fragment. Eros, Carson writes in Eros the Bittersweet, is the god of what in oneself seems lost, when momently found in the beauty of another. “All desire is for part of oneself gone missing.” What’s genius in If Not, Winter is, the loss of the beloved object, the imago, that the poems are about, and the lack the poems in their fragmented state endure, are found to be the same lack, suffered here in flesh and bone, suffered there in ink and surface. I put it better in a review of the book some years ago so I’ll just link now to that.

The line composts the sentence

Carson’s Sappho composts a dozen ways and more. One one student noted is, the enjambed and lightly punctuated line breaks a (propositional) thought into smaller (experiential) thoughts.

And in it cold water makes a clear sound through

apple branches and with roses the whole place

is shadowed and down from radiant-shaking leaves

sleep comes dropping.

The poet composes the line. The line composts the sentence. That’s general to poetry but more prominent here than often it is. “And in it cold water makes a clear sound through” is a whole phase and phrase and frame of feeling. Notwithstanding its unfinish as a sentence. The effect is to reorient thought — to reorient thinking — away from proposition and toward proprioception.

Book and string

This from erikkwakkel:

Smart page with string

These pages from a late-16th-century scientific manuscript share a most unusual feature: they contain a string that runs through a pierced hole. Dozens of them are found in this book. The pages contain diagrams that accompany astronomical tracts. They show such things as the working of the astrolabe (Pic 1), the position of the stars (Pic 4), and the movement of the sun (Pic 6). The book was written and copied by the cartographer Jean du Temps of Blois (born 1555), about whom little appears to be known. The book contains a number of volvelles or wheel charts: revolving disks that the reader would turn to execute calculations. The strings seen in these images are another example of the “hands-on” kind of reading the book facilitates. Pulling the string tight and moving it from left to right, or all the way around, would connect different bits of data, like a modern computer: the string drew a temporary line between two or more values, highlighting their relationship. The tiny addition made the physical page as smart as its contents.

Pics: London, British Library, Harley MS 3263: more on this book here; and full digital reproduction here.