My commentary on The Seafarer for Unlikeness. Long cause I went to Pound. Here’s his Seafarer for you. At the bottom of the post, a special mp3 treat.

For literary translators of OE – for scholars not so much – Ezra Pound’s version of this poem is a watershed moment. His Seafarer in fact is a bearing point for any poet who translates into English; along with the Zukofskys’ Catullus and a couple of other seminal modern works of translation, Pound’s version, first published in Ripostes in 1912, makes later adventurous aberrant projects like Jerome Rothenberg’s “total translations” of Frank Mitchell and David Melnick’s Men in Aida conceivable. This book is nothing like those, but a brief look at Pound’s venture seems fitting, for any translation that comes after must contend with his garrulous and maddening astonishingly rightly-wrong one.

Pound spoke of three ways to freight words with poetic meaning: melopoeia, handling sounds; phanopoeia, throwing an image to the mind’s eye; and logopoeia, setting a word in a special relation to its usage.[1] Three worksites, ear, eye, mind. The trick with Pound’s Seafarer is that he translates faithfully for sound, opportunistically for image, and licentiously with thought. In setting these at the time somewhat scandalous priorities, Pound composed a translation of The Seafarer more objectivist than any heretofore, or probably since, though there have been sorry mimicries many.

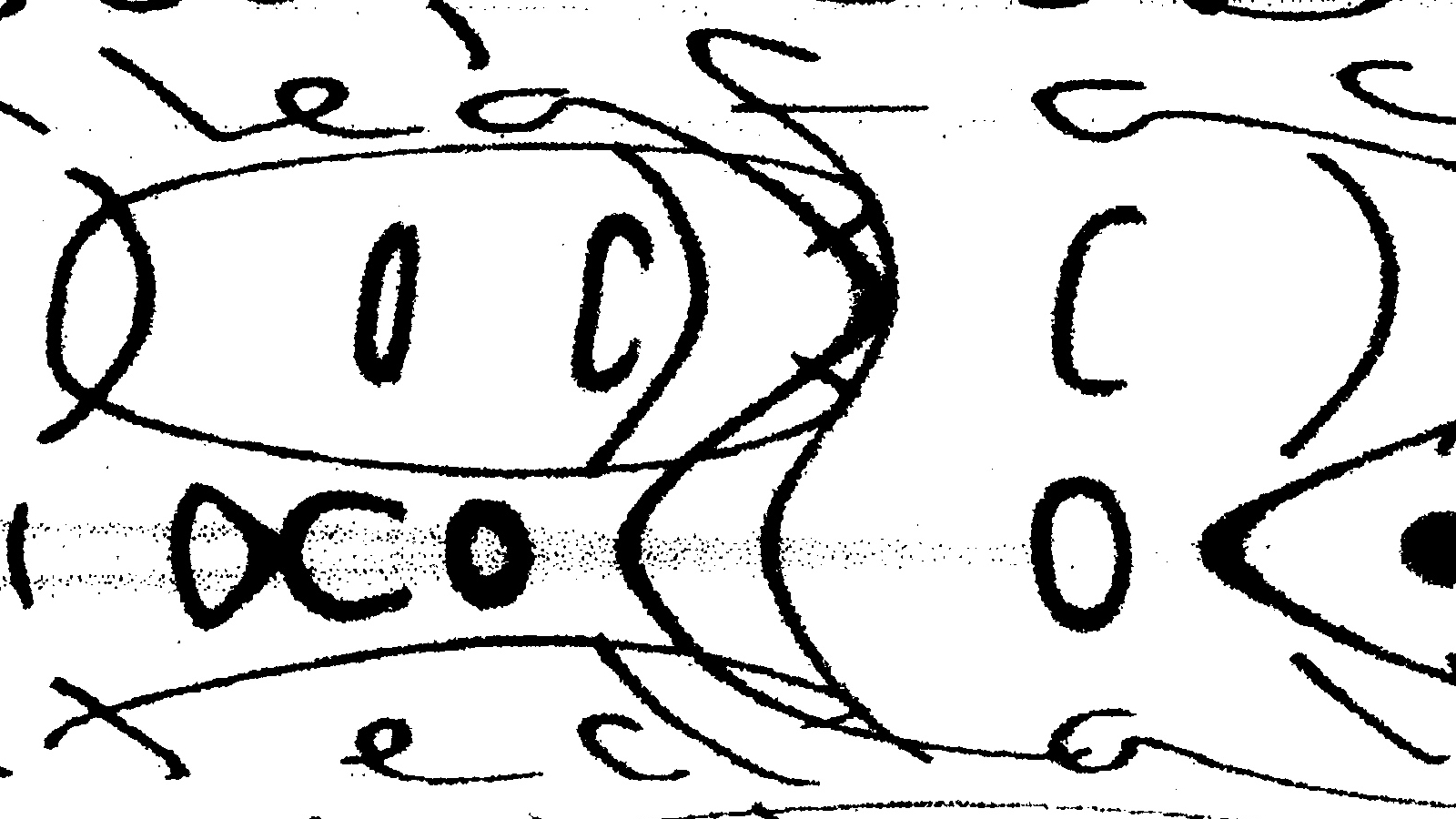

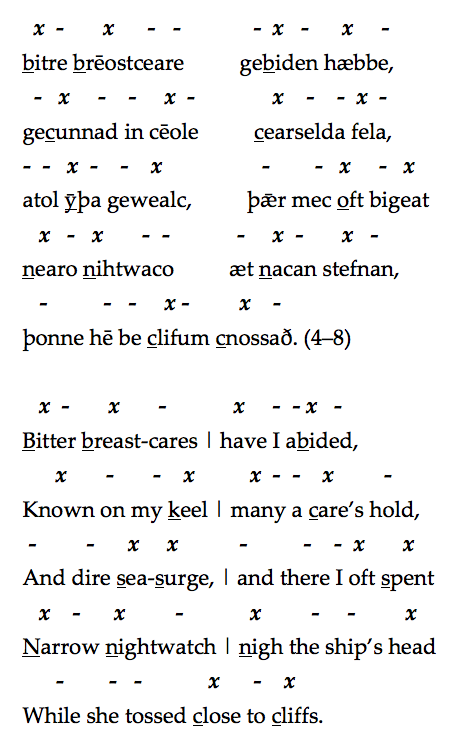

As a patterned arrangement of sounds, Pound’s Seafarer is fidelity itself:

(x = primary stress)

(x = primary stress)

He does far more than catch the feel of the AS cadence – often he keeps the rhythmic form specific to the verse. Where a verse in the source front-loads its stresses, as in bitre brēostceare, Pound’s verse does too, “Bitter breast-cares.” When the source spreads the stresses evenly across the verse, as in gecunnad in cēole, Pound does likewise, “Known on my keel.” When the OE verse reserves the stresses for the end, as in atol ȳþa gewealc, Pound’s verse does that too, “And dire sea-surge.” In this way he captures distinctive effects of the original, as in how the run of lightly stressed syllables before clifum mimes the rush of water towards the cliff. With alliteration, again, not only is the pattern preserved; in most lines the specific sound in the OE poem is kept. Pound translates the internal structure, what Hugh Kenner calls the “patterned integrity” (145), of the AS line; in that given pattern, all its variances, a specific intelligence is to be found, by which articulations of value not otherwise possible, are. Later he’ll speak of the rose magnetic forces shape in steel dust. That insight’s outside our purview, except that the AS poet, his line and his Seafarer’s exile, were clerestory to it.

Phanopoeia – an image thrown to the mind’s eye – means immediacy. In its speed of arrival is the image’s power. In The Seafarer Pound saw an accretive syntax that threw one image then another with minimal interruption:

Stormas þǣr stænclifu bēotan, þǣr him stearn oncwæð,

īsigfeþera; ful oft þæt earn bigeal

ūrigfeþra. (23–25)

Storms, on the stone-cliffs beaten, fell on the stern

In icy feathers; full oft the eagle screamed

With spray on his pinion.

An image is cast on the mind’s eye, another succeeds it, and in their likeness contrast and interpenetration, a new perception arises. Storms beat on the stone cliffs – they fall on the stern – as the former image presses through the latter, the force bearing down on the cliff-face becomes focused on the fragile hull of the boat. Then “In icy feathers” lays, over the brute force of the storm, a sense of something animate, almost delicate; then the feathers of spray, overlaid by an eagle’s cry, become eagle feathers, dimly heard;and then the storm throws its icy-feathered spray on the eagle’s wing, a sort of completion, storm-wing meets eagle-wing, as the sequence comes to rest.

He’s doing Vorticism, a short-lived movement in which he readied himself for The Cantos, in part by conceiving his ideogrammic method, which assayed in words the sort of montage Sergei Eisenstein accomplished in pictures. Both were incited by Ernest Fenollosa’s misapprehensions of the Chinese written character, but like Kenner I think Pound got some of his first stirrings from the Seafarer poet. Either way, it’s a gorgeous montage, one of many in his version, and it arrived as a new possibility for poetry in English. It came though at the cost of turning a bird (stearn “tern”) into the butt of a ship (“stern”).

Later, again using the AS poet’s accretive syntax to cast images in quick succession, Pound shrinks byrig “cities” into berries.

Bearwas blōstmum nimað, byrig fægriað,

wongas wlitigað, woruld ōnetteð (48-49)

Bosque taketh blossom, cometh beauty of berries,

Fields to fairness, land fares brisker

Faithful as a pup to sound, brilliant opportunist with image, Pound looks kind of slobby with what the words “actually mean.” And though in the abstract we may agree a poem’s meaning lies mostly outside its words’ denotations, we’re like to cry foul when dictionary sense is just forgot.

“reckon” (1) from wrecan, “recite”

“shelter” (61) for scēatas, “surfaces” or “corners”

“on loan” (66) from læne, “fleeting”

“twain” (69) for twēon, “doubt”

“English” (78) for englum, “angels”

One or two are felicitous; more look like gaffes; did he really just write in the ModE word the OE word reminded him of? We can maybe find justification for any given departure. This one was made to preserve the rhythmic or the alliterative fabric; that one refuses the connective tissue that would set images in logical or causal arrangements; angels are demoted for the same reason the devil is erased later, to draw the poem back to what Pound thought were its pre-Christian origins. But the glary errors, taken together, suggest Pound didn’t care so much for the semantic values of the poem’s words – not as he cared for the sound matrix they were in, or for the image cascades they composed.

He sacrificed sense to hold a sonic form, or to sharpen an image sequence. He valued those most so he translated them foremost. Or, is it that word, image, sense were on an equal footing, another unwobbling stool, but loss of sense stands out most to us because symbolist reading habits make us meaning junkies? We may be as eager for a semantic meaning as the Seafarer is for a transcendent one, as ready to travel off in mōd from our embodiment, ear’s wonder, eye’s honey, to an abstract immaterial construction elsewhere. That was the temptation Pound spent his long cracked terrible beauty of a poetic life arguing tangibly against.[2]

The poem calls its abstract immaterial construction “Heaven.” The moment the poem commits to it fully, it also happens to turn a page – and Pound stops right here. Cuts the last 23 lines of the poem. He was sure they were the work of some later pious other. And he wasn’t alone in wanting to save an ostensibly pagan original from a later Christian overlay. His and others’ evidence: Right where folio 82v ends, the sentence ends too, and also the larger thought. Start of the next folio, hypermetric lines set in; pious commonplaces start to pile up; arguably, poetic invention falls off. And so more than Pound only have concluded The Seafarer is cut off by the loss of one or more folios, and what picks up on what’s now 83r is the middle some other, less interesting poem.

But the sudden shift to an earnestly Christian homiletic register would not have jarred an AS audience the way it does a modern reader. A lot of the impetus to break the poem in two came in the late 19th C. from scholars who wanted to recover a heroic pagan Germanic literature in its “pure” condition. While that drive has long since thankfully died, the case that the poem is interrupted, a chimera, has not yet quite. Pope and Fulk:

[T]he shift at this place from the specifics of a retainer’s sad condition – the approach of decrepitude, the loss of a lord, the futility of burying gold with the dead – to a passage of mostly devotional generalities, in conjunction with a sudden change to hypermetric form, raises the possibility that The Seafarer is not one poem but fragments of two. It is not necessary to read the text this way … but unity of design is by no means assured. (102)

They like the question for displaying a sort of indeterminacy special, they say, to OE studies, with its single copies of poems handwritten by error-prone scribes in frangible manuscripts. And I’m not one not to cheer twice for indeterminacy. Still, I see a single poem, a single author. The shift to hypermetric (six-stress) lines doesn’t last long, and such lines come and go in a number of the Exeter poems. The switch to a homiletic register fits the dramatic, emotional, and spiritual arcs of the poem, and is consonant with other poems of its ilk. And the closing lines do have poetic force, something in places quite majestic. Yes, the last few lines are sententious, but other OE poems of the first order have like passages; and as I note below, the scribe does quietly set them a bit apart. I see nothing out of fit here, just ordinary variousness.

The seam at the end of the folio (l. 103) is just one of the aporiae that have thrown the poem’s unity into doubt. Another is that its sea voyage seems literal at the outset, full of material details that resist the calculus of allegory mind—an ice-clotted beard, a mew gull’s cries; and yet misfires in the Seafarer’s discourse around the voyage start to invite figurative reading and to load the journey with allegorical freight; and yet, as one ventures into allegory, the voyage itself disappears from view, not to be seen again. How to reconcile these signals and keep the poem one poem? Whitelock has argued (Pope and Fulk 100) that the journey is literal from start to end; religious self-exile and pilgrimage were actual AS cultural practices, and this is a composite account of such a journey. Conversely, for Marsden, the journey stands from the start for the Augustinian pilgrim’s passage from the earthly to the heavenly city; the Seafarer’s exile is not from the towns of men, but from Heaven, whence he also is bound (221). I take a middle position, feeling the poem morphs from literal to allegorical: the journey begins as an actual journey, full of resistant earthly textures, and gradually, thanks in no small part to the misfires around forþon crying there’s more here than meets the eye, metamorphoses into journey as allegory. The journey journeys. It’s subtle, there being no one point where we can say the journey has changed its nature, from literal to figurative. The transformation is as mysterious, imperceptible, and I think maybe undeniable as the metamorphosis the pilgrim aspires to.

A third aporia is the speaker’s ambivalence towards sea voyaging. He hates it, loves it, loves to hate it. At sea he longs for the delights of human company. Among men and women he thirsts for his cold hard life at sea. His ambivalence, and especially the pressure he puts on the word forþon “therefore” – which seems sometimes to mean just that, and sometimes about the opposite, “even so” or “just the same” – have vexed readers who want a unitary speaker, leading some to treat the poem as a dialogue. Frankly, as a poet who makes his living off mixed feelings, I have trouble seeing the problem. Keats, Negative Capability, solved. More interesting is that it’s been an interpretive problem in the first place. Belonging to print and internet cultures, we’re attuned to certain ways of rendering mixed feelings – synchronic ways, mostly, particularly irony, where one attitude is layered over another, with gaps for the underlayer to show through. Think George Eliot, Jordan Abel, a well-crafted tweet. In The Seafarer oral storytelling conventions persist, and oral traditions don’t, to my knowledge, use irony to create interiority. Some, though, convey mixed feelings diachronically. In The Odyssey, the consummate seafaring story as it happens, when Telemachus expresses two conflicting feelings adjacently, it’s not a contradiction or a change of heart, but a two-step account of an inner conflict: the poet describes one feeling, then the other, and his audience knows they cohabit in the young man’s mind. Some of what seems like self-contradiction in The Seafarer may be the work of unfamiliar narrative conventions. And some of it is the AS poet’s use of logopoeia in putting forþon in a torqued relation to its ordinary usage.

There are two capital letters in the MS, both near the end of the poem, and I’ve broken the OE transcription into verse paragraphs accordingly. I don’t posit a new speaker for the final lines, let alone for the closing “Amen,” but rather the same speaker putting on the new voice he has aspired to the whole poem.

Phew. Thanks for hanging in there. Just the first lines of mine …

THE SEAFARER

I can from myself call forth the song,

speak truth of travels, of how, toiling

in hardship, hauling a freight of care,

I have found at sea a hold of trouble

awful rolling waves have, too often,

through long anxious nightwatches

at the prow, thrown me to the cliffs.

My feet, ice-shackled, cold-fettered,

froze, even as cares swirled hot about

my heart and inner hungers tore at

my sea-weary spirit. You can’t know

to whom on land all comes with ease

how I, sorrow-wracked on an icy sea

wandered all winter the way of exile,

far from kinsmen, my hair and beard

hung with ice, as hail fell in showers.

I heard nothing there but sea-surge

and icy surf, swan song sometimes,

took the gannet’s cry and the voices

of curlews for human laughter, made

the call of a mew gull my honeymead;

storms beat at stone cliffs, icy-feathered

the tern answers, a dew-winged eagle

screeches; no sheltering kinsman here

who might console a desolate spirit.

And, special treat! Ezra Pound reading his translation (with drums).

[1]. You can still charge words with meaning mainly in three ways, phanopoeia, melopoiea, logopoeia. You use a word to throw a visual image on to the reader’s imagination, or you charge it by sound, or you use groups of words to do this. Thirdly, you take the greater risk of using the word in some special relation to “usage,” that is, to the kind of context in which the reader expects, or is accustomed, to find it. – ABC of Reading (37)

[2]. I have tried to write Paradise // Do not move / Let the wind speak / that is paradise. – The Cantos (822)