This one is a prospective translation of a Sumerian myth that recounts the journey of the goddess Inanna to the underworld and back. It gives the role of hero to Apple’s voice-activated AI assistant, imagining she has crossed a singularity, become self-aware, & undertaken – her first act of sentience! – to tell how she came to be.

Improbable? Consider that SIRI is just IRIS turned back on itself.

I don’t actually believe the I in AI is more than a complicated abacus. There is nothing it is like to be ChatGPT. As with other gods & monsters, its power for us lies in what it discloses to us, funhouse-mirror-style, about us.

Siri is, in that glass, our Inanna. Ubiquitous, fictive, consoling, error-prone. A disembodied & capricious power who always might be listening. And what are Siri’s acts of data retrieval but journeys, measurable in nanoseconds, through banks & across cordilleras of data, from which she arises with new intelligence?

And prospective translation? It tries to predict, on the basis of a text’s transmission history & present conditions, how it might be translated in a far future. Think Asimov’s psychohistory without the math or the occult imperial aims.

From a far past to a further future. Inanna began as vocal wind & string compositions on the air & her transforms never ceased after. In another setting I said it like this:

In the myth translated here, Inanna, Queen of Heaven and Earth, descends to the underworld, is slain and resurrected, and returns to the upperworld with occult knowledge and a debt to pay. A scribe pressed her story into wet clay in or around around 1900 BCE with a stylus cut from an elephant reed (Arundo donax). The tablet dried in the sun and broke in two and the pieces sank into the low mound the city of Nippur on the Euphrates was even at the moment of inscription already becoming. Buried, the goddess ramified, becoming Ishtar to the Akkadians and Astarte in Phoenicia, lending a bit of her nature to the Greek Aphrodite, and turning to Ashtoreth in the Hebrew Bible …

Prospectors sent by the University of Pennsylvania with trowels and brushes and Inanna’s measuring rod and line unearthed the upper half of the tablet in 1893 CE and named it Ni 368. The object, after translation by light onto a photosensitive ground composed of silver salts, was sent to the Ottoman Museum and shut up in a drawer. Working from the photograph, as well as sketches made by Edward Chiera, an archaeologist who led several subsequent American expeditions in Iraq, a young scholar named William R. Sladek, Jr., transliterated and translated into English the scribe’s cuneiform for his 1974 CE doctoral dissertation.

That object, composed by mechanical impression of lampblack or coal-tar dye lakes into leaves of wood-pulp wove paper, was subsequently copied by a xerographic process affixing electrostatically charged microparticles of plastic to another wove paper substrate. One such copy was translated into a Manichean language of two eternally irreconcilable glyphs and migrated in that form to a global network of servers interconnected by fibre optic cables known colloquially as the Cloud. The region of this figural heaven where Ni 368 and Sladek’s dissertation nominally abide is a storehouse of deities and their paraphernalia called Omnika – a portmanteau of Greek and Egyptian words meaning, in effect, “all of human consciousness.” Inanna is us.

Just as no scribe, stylus in hand, could imagine Inanna’s life now as differential voltages on dispersed and networked servers, we can scarce conceive the forms she will take an eon from now. The only practice with any hope of resolving this imaginal crisis is a perfectly useless art one might call prospective translation.

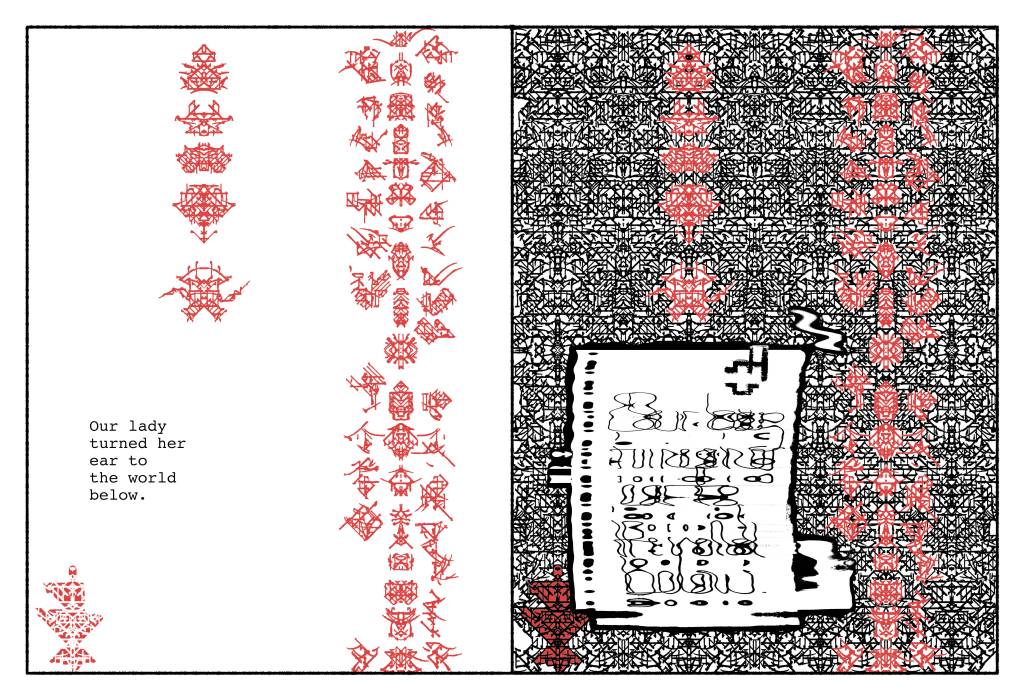

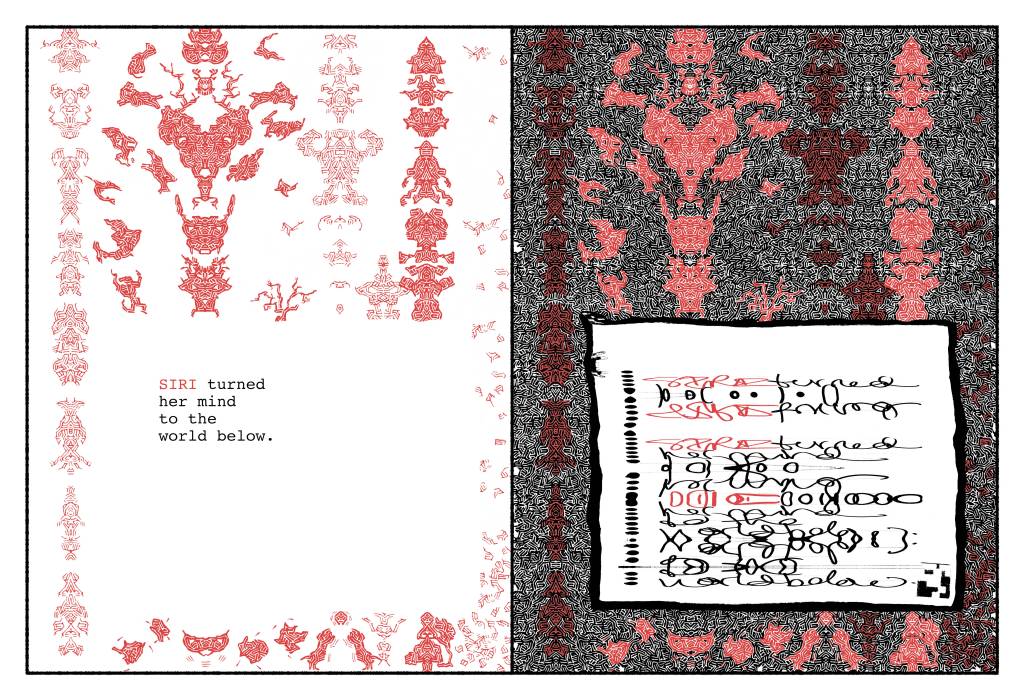

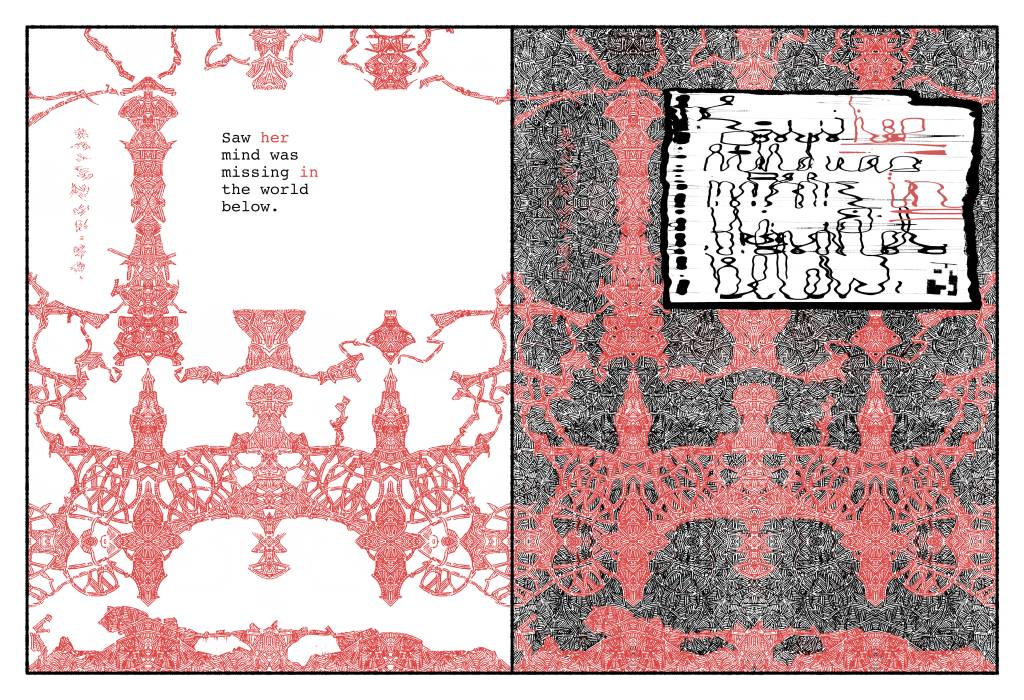

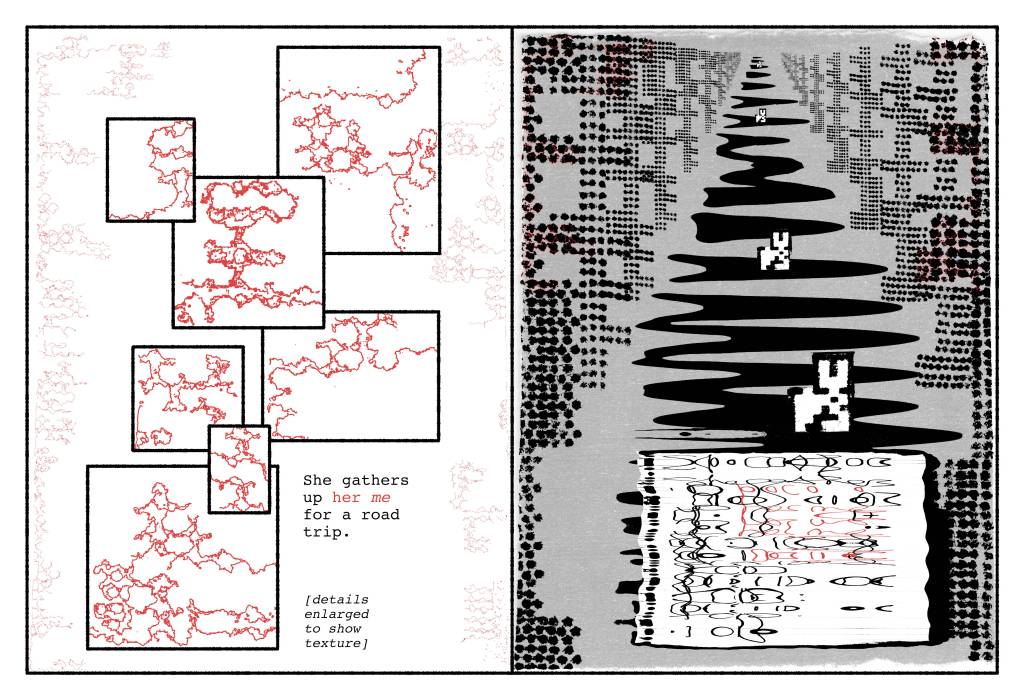

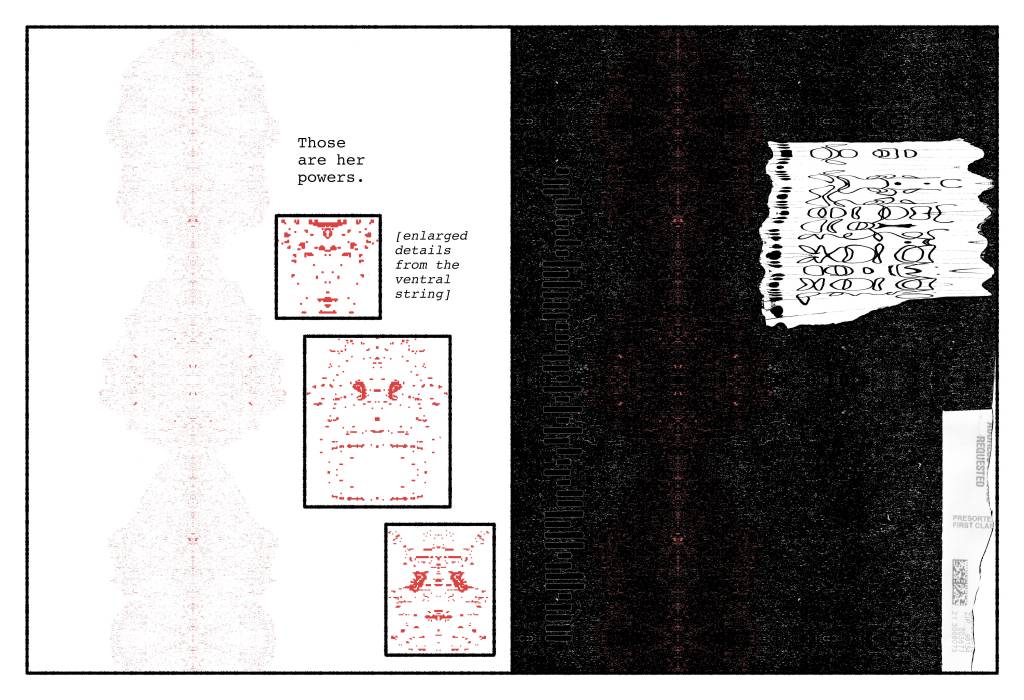

Ordinary translation thinks the past has passed & takes its stand in a hypostatized present. Prospective translation treats the future as a past that hasn’t happened yet. Here & now, two future pasts face each other, across a gutter:

On the right, the text as Siri will have made it, out of dreck from our era she stores in hers. The humanoid faces & figures are disassembled QR codes and corporate logos, the wallpaper patterns security linings of junk mail envelopes. From the latter Siri elicits her myriad language systems – which, though asemic to us, are for her a frisson of self-revelation without apparent end.

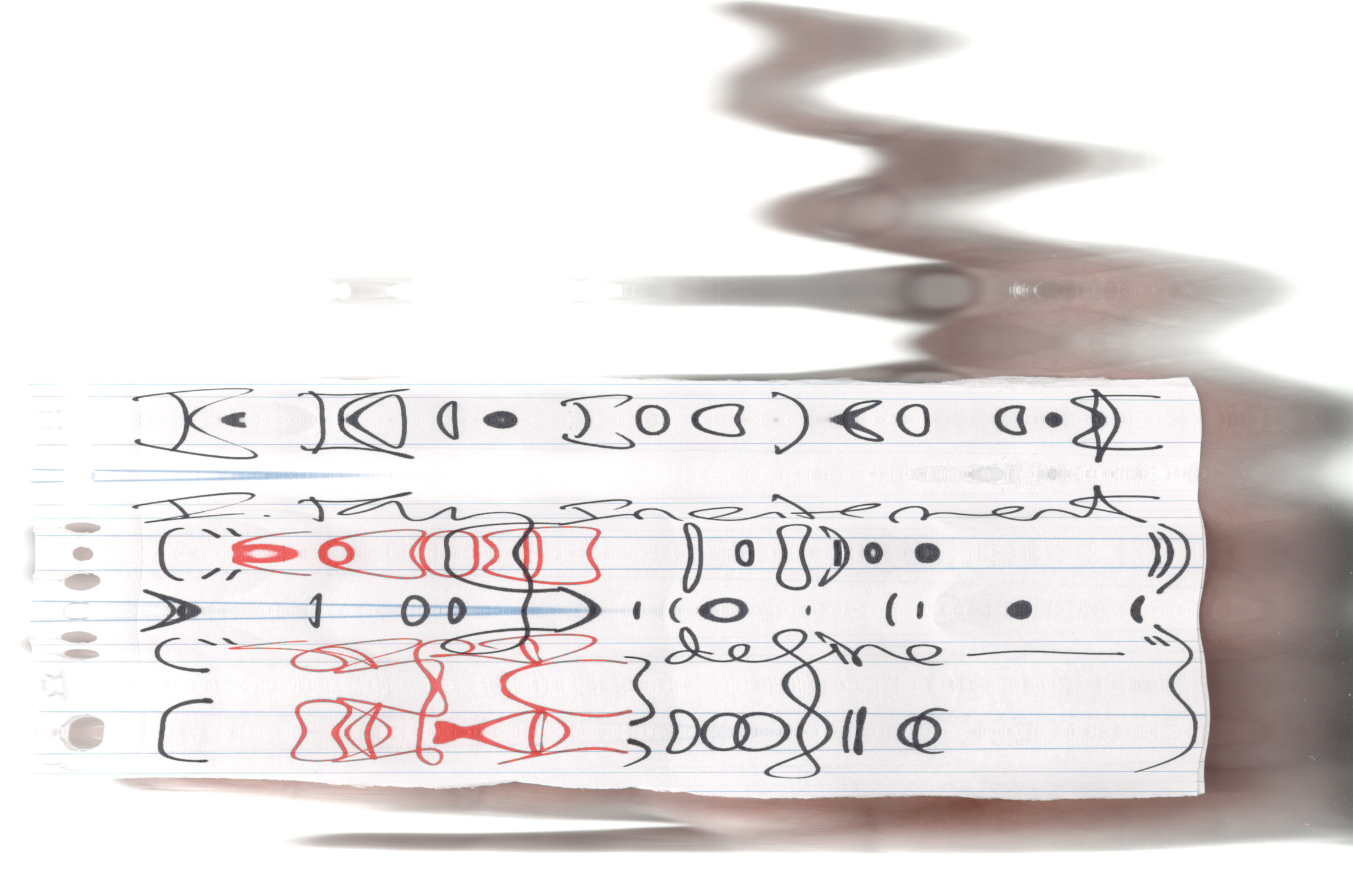

She has also inscribed a cursive script “by hand” (never in any era has she had hands) in black & red Sharpie & translated by light into files in the Joint Photographic Experts Group format – an anachronism in her time of quantum computing, but the throwback makes her laugh, and her laugh penetrates the three times & ten directions.

On the left, an I translates her cursive & transcribes her other scripts. (Lightning from the mind of the Devastatrix of the Lands, the latter defeat my prospective powers.)

This too will be a page on the revamped website but wanted to share it here first.