Description for a spring course I’m way excited to teach again.

We know Ezra Pound and William Carlos Williams for a few hit singles

The apparition of these faces in the crowd.

…

so much depends

upon

and maybe a few sayings fit for a bumper sticker. Go in fear of abstractions. No ideas but in things. What these soundbites miss is each poet’s complex and ongoing self-reinvention. Both started as Imagists, rejecting the sentimentality they found in late Victorian verse, instead carving small hard moments of perception. From there, the two diverged, Williams becoming more invested in the local, the scruffily irregular, Pound in archetypal patterns that for him made ancient history current, distant cultures present. Both remained committed, however, to reinventing the epic, and to bringing mythic awareness to the crush of modernity.

Pound read mythology as if it were the morning newspaper.

Williams read the morning newspaper as if it were mythology.

—Donald Revell

Between them they initiated strands in the web of American postmodernism that continue to spread and bear fruit and further ramify to this day. Be ready for close reading of sometimes very difficult texts; the postmodern epic, there’s no mastering it, only entering and being swept through and by it. Assignments will include regular critical responses; a seminar paper to be presented to the class and revised for final submission; an allusion chart mapping a chosen passage from The Cantos; and line-by-line meticulously close reading of a chosen passage from Paterson. Our texts: Pound, selected early poems from Personae, Cathay, selections from the Cantos, selected critical writings; Williams, selected early poems, Spring and All, Descent of Winter, Paterson books I-III, selected prose.

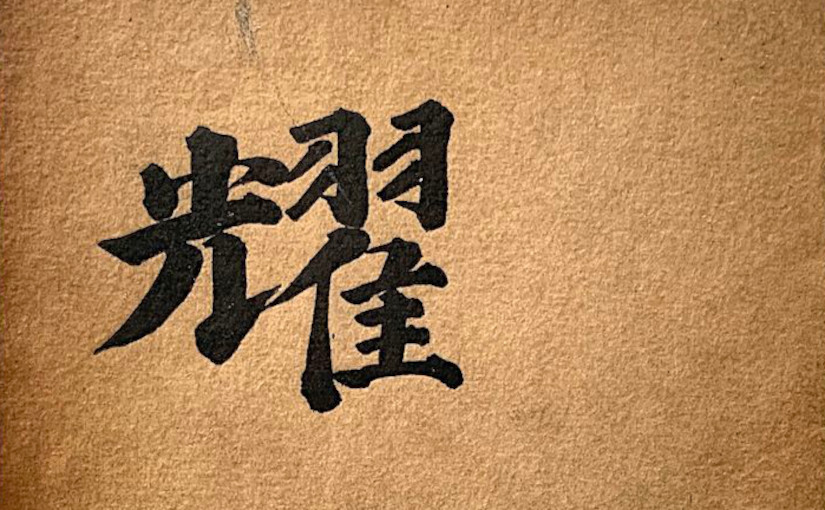

The image atop, a detail from Eight Views of the Xiao and Xiang Rivers (Sho-Sho Hakkei) by Sesson Shukei (1504–ca. 1590). A time-honoured theme in Chinese and Japanese landscape painting; one such series was inspiration for Pound’s “Seven-Lakes Canto,” Canto XLIX, still point in the book’s burning wheel.

Not, as far as I know, Shukei’s; it’s just for instance. The whole of it