Last fall, in my Curatorial Practice course, I worked with five other students to propose an exhibition of contemporary installation art by women. We chose works that investigated the domestic sphere in diverse and exciting ways. Inspired by Foucault’s notion of a “heterotopia,” a space where norms are suspended to make new perceptions possible, we called our exhibition Otherspaces.

It was a fictional exhibition, so we dreamed big, imagining we had the social capital to land big-name artists and the funding to secure and adapt our ideal space: an airplane hangar (where planes sleep and are fed when home from other places) in which we would build a stage-set house with a room for each piece.

Each of us also wrote a curatorial essay for the show. Some wrote on the feminist dimensions of the works. Some explored the works as other spaces where the familiar is made strange. I like to think of an exhibition as a collaborative, multimodal, interactive work of art, so my essay reads Otherspaces as a poem made of things.

It is / here / it is.

Speaking with Things

To be and to know or Being and thought are the same. – Gerard Manley Hopkins, on Parmenides (Robert Bringhurst trans.)

I’ve been thinking lately about words as things. Words exist physically, as grooves in stone or electrons on a screen, and they have physical effects: striking your retina or eardrum, they induce limbic arousal, or a surge of oxytocin, or a protest in the streets of a capital.

We know some things speak – any thing used as a word does. Things may also speak at other times, as themselves, of the inner life of matter. If that sounds merely poetic, recall that physicists are talking these days about physical events as acts of information exchange.

In Otherspaces, artists ask how things may work as words, in a language humans and objects co-create. And they hint that things work with us in this way because of something thoughtful about them, and their participation in our inner lives.

1. Rooms

This ocean, humiliating in its disguises Tougher than anything. No one listens to poetry. The ocean Does not mean to be listened to. A drop Or crash of water. It means Nothing. It Is bread and butter Pepper and salt. The death That young men hope for. Aimlessly It pounds the shore. White and aimless signals. No One listens to poetry. – Jack Spicer, “Thing Language”

“Thing Language” is a one-stanza poem. Stanza comes from the Italian word for “room.” The poem is a one-room house where words are taken for things.

It insists, by disjunction, non-sequitur, and its roughhouse actions at the line end, also by pretty much saying so, that its words don’t mean any more than the ocean, salt and pepper, or death do.

Of course, the words do mean, in that they refer to concepts, but that kind of meaning doesn’t exhaust their function. They have another kind of significance too. Consider the difference between “I know what you mean” and “you mean a lot to me.”

Otherspaces is a six-stanza poem that speaks with things.

Begin with a blank: white walls, white floor, white ceiling, white furniture. It’s not hard to see it as a tabula rasa, a blank slate, such as we once thought the mind is at birth, waiting to be marked by thought.

Visitors to Yayoi Kusama’s Obliteration Room are handed sheets of stickers and asked to place them on surfaces however they wish. Some make geometric patterns that recall those grids of dots on paleolithic cave walls. Others tag a surface with their own name. Many make a beautiful mess a bit outside their control, à la Pollock or Cage. Being participatory, the piece is also aleatory, allowing chance into its composition. By gradual accretion, a dead pure blank empty sterile white space acquires the marks of human use, human habitation.

Each sticker is a trace of a mental act – a speech act. Artist, visitor, and sticker all help to utter it, though the artist has left the room. After the visitor leaves, the sticker continues as a record, a record that becomes unintelligible in the babble of so many others. It’s like a marketplace in which you hear intersecting rivers of human speech and cannot make out a single word.

Traditionally the origin of Chinese logograms was traced to bird tracks in river sand. A language, whether of sound, gesture, picture, symbol, or object, is always a human-nonhuman hybrid – human and air, human and clay and wedge, human and electron beam. These Otherspaces are full of chimaeras.

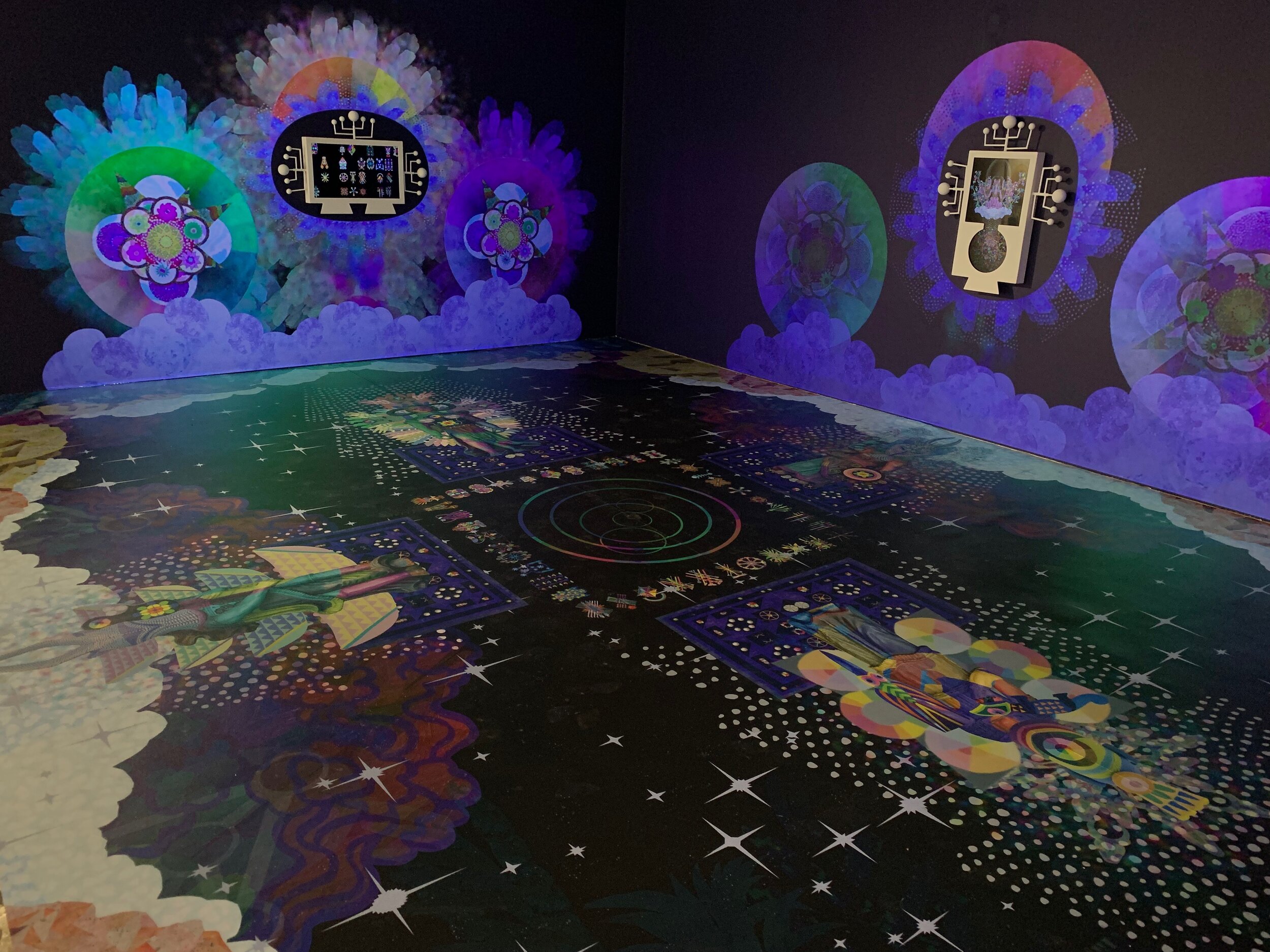

Saya Woolfalk’s Empathic Cloud Divination envisions a post-human future of soul uploads to the Cloud and teachings of human-plant hybrids. Semi-abstract patterns cover the floor and walls. From the ceiling, projectors throw kaleidoscopic displays over the room’s surfaces. They are the minds of astral beings (Empathics) taking a physical form congenial to them. (Greek gods and Milton’s angels did the same.) Boxes like computer screens on the walls show glyph-like objects suggesting, as asemic writing does, a possible yet unparsable language.

Woolfalk’s matriarchal Afro-futurist vision offers rest from the peripatetic gazing one so often gets lost in a gallery. Beanbag chairs invite reverie and a respite from all the thoughts of self and other, past and future, getting and spending, that typically populate us.

Tracey Emin’s My Bed is a centaur: one’s head on another’s torso. A painting on the wall, Turner’s Rough Sea, looks over its shoulder in astonishment at a dishevelled bedroom, its new body.

The piece depends not so much on the room’s surfaces as on its function – the acts, thoughts, feels and words we sense a room is for. A bedroom – therefore, intimacy, sleep, dream, waking, and private emotions.

Bed and painting together make what Ezra Pound called an ideogram. The ideogram is a way of saying concretely something unsayable otherwise.

You make one by joining two or more tangible realities. Making a poem you conjoin verbal images. Making a film you conjoin photographic images and you might call it montage. Both practices trace back to a (mis)understanding of the Chinese ideogram because both are ways of speaking with things.

When you do it with objects you have an installation. Emin uses things – a painting, a bed strewn with tissues and coins and condoms – the way Pound thought pictures of things were used in written Chinese. (He was wrong about Chinese but right about how a poem can work.)

Whatever joins the sublime mess of storm in the painting, to the messy abyss of grief on the bed, is not sayable another way. The painting and the bed “speak to each other,” as the saying goes.

2. Objects

My essay is an attempt at an ideogram – its strokes six artworks, two poems, and an inkling.

Plates and a dinner set of colored china. Pack together a string and enough with it to protect the centre, cause a considerable haste and gather more as it is cooling, collect more trembling and not any even trembling, cause a whole thing to be a church. – Gertrude Stein, “A Plate” (“Objects” 15)

Stein enters the inner life of objects. From the outside, a plate is a plate. Inside, it is stained by experience, and bears knowledge of its own formation and destruction. Were it sentient, its thoughts might move at about the speed its molecules quiver at – string | haste | cooling | trembling. The poet’s own voice enters at the end: “cause a whole thing to be a church.”

Formerly, our access to the inner life of objects was sacral. For a Modernist like Stein it’s hieratic and indeterminate. Today, it grows scientific, in the form of Integrated Information Theory. I doubt any of the artists here would use any of these terms. But each endows objects with something lifelike from which they are equipped to speak.

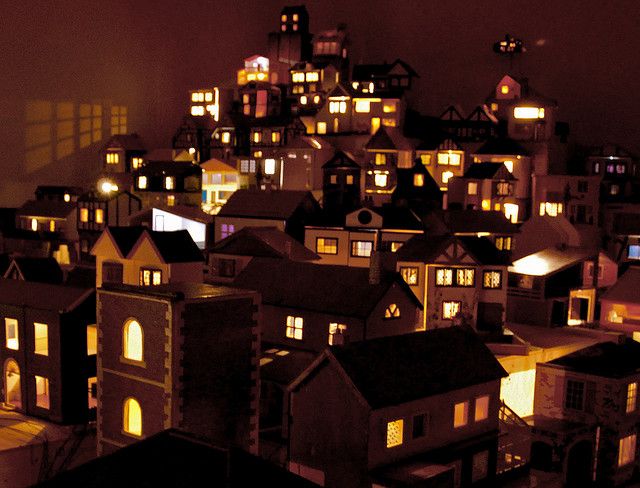

We’ve looked at things put in rooms. Rachel Whiteread’s Place (Village) is rooms accreted as things.

The work’s an assemblage of 150 doll houses collected over twenty years. The Victoria & Albert Museum, which has lent it to our imaginal exhibition, describes the houses as “devoid of both people and objects.” There’s no furniture, but there are carpets, wallpaper, curtains, and artwork on the walls.

The windows of these houses are lit with life – maybe it’s the houses’ own sentience. Try seeing the windows as eyes looking back. Once you have, you can’t unsee it.

The happy variety of rooflines affirms their diversity. Curiously, the V&A finds a “haunted atmosphere” here. What’s a haunted house but a site where our repressed sense the objects we’re aware of are aware of us leaks out of the mental basement?

One can imagine entering one of the rooms here – possibly to find a gallery like this one. It’s a nested arrangement. So too of course is Otherspaces: a hangar, etymologically a “house yard,” holds a house, the house holds rooms, a room holds a village.

In The Poetics of Space, his study of the “oneiric house,” the house of dream-memory, in his chapter on nests, Gaston Bachelard writes:

If we were to look among the wealth of our vocabulary for verbs that express the dynamics of retreat, we should find images based on animal movements of withdrawal, movements that are engraved in our muscles. How psychology would deepen if we could know the psychology of each muscle! And what a quantity of animal beings there are in the being of a man! But our research does not go that far. (91)

Neither does ours. Just a bit further is good though.

Like Whiteread, Chiharu Shiota works in miniature. Claude Lévi-Strauss writes of miniatures in his essay on the “science of the concrete”:

A child’s doll is no longer an enemy, a rival or even an interlocutor. In it and through it a person is made into a subject. In the case of miniatures … knowledge of the whole precedes knowledge of the parts. And even if this is an illusion, the point of the procedure is to create or sustain the illusion, which gratifies the intelligence and gives rise to a sense of pleasure which can already be called aesthetic. (24)

In the same essay he describes the artist’s work as halfway to bricolage, “making do with what is at hand” – think Duchamp’s chimaera of stool and bicycle.

In Shiota’s Connecting Small Memories, little wholes are made parts in a constellation. They are found wholes, so this is bricolage. Small objects – toy chest of drawers, washing basin, rocking horse – are linked by threads, as if, her title suggests, our thinking were material and external to the mind.

Of course, it could simply be that physical objects symbolize mental objects, and their assemblage stands for something mental. Dig deeper, though. Shiota’s piece touches on the participatory quality of perception – how the object helps constitute our subjectivity. The threads here don’t just represent, they perform, acts of mental association.

How? Your eye follows the thread from one thing to another, and as it moves in its circuit, your mind does psychically what the objects do physically.

That makes a false distinction though. Try instead: The physical objects threaded together are mental objects threaded together. You know it because you enact it.

In A Subtlety, or, The Marvellous Sugar Baby, Kara Walker makes the Sphinx, a creature of the desert wastes, domestic twice over. It wears a skin of sugar, that ordinary kitchen substance, with slavery and the global commodities trade curled at the bottom of the bowl. And its visage is the stereotypical Mammy figure, the hale and happy house slave whiteness imagines devoted to its needs.

Walker first installed the work in a disused sugar factory, calling it “an Homage to the unpaid and overworked Artisans who have refined our Sweet tastes from the cane fields to the Kitchens of the New World” (Creative Time). To set it in a courtyard, as we have, domesticates it a third time: a courtyard is a yard within a house, an outside brought inside, as paradox, an intimate other.

And it is another chimaera: a sphinx made by joining human head and torso to lion haunches and paws. In this guise it appeals for its power both to the Great Sphinx at Giza and the Greek one riddling Oedipus.

The former is monumental stone built by slaves. Here it bears the righteousness of peoples oppressed by slavery and global capitalism to the heart of the colonial house it gives the lie to.

The latter crouches there asking mortal questions of a tragic entitled ruler. Styrofoam and sugar become stone that speaks, intelligent matter, but what riddle?

More about & by each artist

The image atop is a picture of Yoko Ono’s Half-A-Room.